Scientists and community members in Altadena are testing ways that California species can assist efforts to rebuild

Driving through Altadena today, visitors might pass a lone house—bordered on both sides by empty lots—miraculously missed by the ember storm that took its neighbors. Above, the horizon is marked by the striking chaparral mountains of Eaton Canyon—still charred and covered with sparse shrubs.

About nine months ago, the Santa Ana winds spread intense fires that rocked the sprawling Los Angeles metropolis. The Pacific Palisades Fire on the west side of the city and the Eaton Fire to the northeast combined to destroy more than 16,000 structures. Throughout the areas burned in the Eaton Fire, the foothills community of Altadena was among those hit the hardest.

The nearby mountains, with their numerous hiking trails, plants and animals, were what drew many residents to this L.A. enclave in the first place. Now that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has wrapped up the last of its fire debris removal, community members are exploring ways to rebuild—and in light of Altadena’s natural beauty, some are looking at ways to do so by incorporating native plants.

Researchers have uncovered that certain native species may aid in fire resiliency and in cleaning up contaminated soils after a blaze. In Altadena, scientists and community members are now working together to restore these plants to the landscape.

Understanding the chaparral

The chaparral, California’s most prevalent plant community, is characterized by shrubs that bloom as early as late winter and into the spring. California lilacs cover the hills in a deep blue. Manzanitas—fruit-bearing shrubs or small trees—show off their burgundy red trunks. And the delicate, white blossoms of chamise shoot up from beds of green.

Despite its local prominence, the chaparral is a deeply misunderstood ecosystem. At first glance, the mountains’ patchy shrubs look far from the deep green canopy people often associate with high biodiversity. However, chaparral environments actually hold a stunning amount of biodiversity. Hundreds of species call the chaparral home, including California icons such as the quail, poppy and cougar.

Chaparral shrublands are also huge reservoirs for carbon sequestration, according to Robert Fitch, a fire ecologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. And the chaparral’s woody shrubs have roots that can penetrate deep into the soil, creating channels that help groundwater get recharged during rainstorms.

But perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of the chaparral ecosystem is its relationship to fire. Myths about the chaparral and fire run so deep that the California Chaparral Institute has a webpage dedicated to dispelling them. Among these myths is the idea that the chaparral “needs” frequent fires to renew itself—and that to save communities on the wildland-urban interface bordering a chaparral ecosystem, this vegetation must be cleared.

Indeed, the chaparral is uniquely adapted to fire in that some of its shrubs require wildfires to germinate. The seeds from manzanitas, for example, begin to germinate when triggered by chemicals in wildfire smoke, while the seeds of Ceanothus—the California lilac—are triggered by heat. “If you go into a chaparral area the following spring, after the fire, there’s very often vast fields of wildflowers,” Jon Keeley, a fire ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, says. “And those wildflowers comprised maybe 20 or 30 different species, and most of them were not present prior to the fire, and in fact, weren’t present since the last time there was a fire.”

But the diagnosis that chaparral needs fire indiscriminately is misleading, says Richard Halsey, a chaparral ecologist and director of the California Chaparral Institute. For one, chaparral’s adaptation is more accurately characterized as a sensitivity to certain types of fire. “It has to come at the right time of year, which is typically in the fall; it has to come at the right frequency, which is no more than once every 30 years, and it has to burn extremely hot,” he explains.

Too much fire is harmful to the chaparral ecosystem. Many chaparral shrubs take 15 to 20 years to reproduce, and when wildfires happen too frequently, the ecosystem degrades, leaving it more vulnerable to the growth of flammable, invasive grasses.

Since 2000, California has experienced a sharp rise in wildfires amid a long-lasting drought and climbing air temperatures. In 2024 alone, more than one million acres were burned by about 8,000 wildfires. Many of these fires are caused by human ignition—like electrical equipment, cars or fireworks—then driven by wind. The only source of natural ignition for a wildfire is lightning, which Keeley says is a rare occurrence in Southern California. What made the Palisades and Eaton fires unusual was the sheer amount of urban damage they caused, fueled by exceptionally strong Santa Ana winds. But the fires weren’t at all unique to the chaparral ecosystem, as they fit within its natural fire regime of every 30 or more years.

In the next few decades, another chaparral fire will certainly ignite in the area. And the region’s fire-adapted vegetation might help people living near these wildlands to better protect themselves.

How native plants can aid fire resilience

California buckwheat, when planted widely spaced and regularly watered, can help provide a high-moisture buffer around homes to limit fire. Dick Culbert via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.0

Nina Raj moved to North Pasadena—right on its border with Altadena—because of the access to nature provided by the nearby Eaton Canyon. Raj, who volunteered as a docent naturalist at the Eaton Canyon Nature Center before the fire, tended to the ground surrounding the center to better connect with the local environment. As she evacuated her home during the Eaton Fire in January, a sense of responsibility for the native plants in the region compelled her to save their seeds, which she had collected from the nature center over the years.

She had also been storing seeds as part of the Altadena Seed Library, which Raj started in 2021 as a way to share seeds from the native plants she was tending to around her home. She packaged seeds of Cleveland sage, palmers, Indian mallow, California Buckwheat, coyote brush, artemisia and more. Then, Raj put some of these packages in seed exchange boxes—think of Little Free Libraries but with seeds—around town, which neighbors could add to and take from to plant in their own yards.

Now, Raj has turned some collections of seeds into care packages for people who lost their homes, so they can grow native plants when they rebuild. On top of a full-time job, Raj runs the library in her spare time, working with seeds contributed by community volunteers.

These native plants, according to recent research, can foster greater fire resilience in urban communities. A 2020 study by Keeley and others, published in the Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, described “defensible space” as key to protecting homes from impending wildfires. Defensible space is a buffer between one’s home and potentially flammable plants, but it doesn’t have to be space that is completely cleared of vegetation.

One way in which homeowners can create defensible space, according to the study, is through a careful utilization of native plants in the form of greenbelts. With this strategy, certain native plants—such as California buckwheat and sage brush—are widely spaced and regularly watered to maintain a high moisture content and prevent ignition.

Trees may also act as natural shields to protect houses from airborne embers, according to Halsey. Oak trees with a high moisture content might be particularly effective, Keeley adds, but this phenomenon is still being researched. He says that in the case of the Eaton Fire, where the Santa Ana winds reached 60 to 70 miles per hour—roughly double their normal speed—the chances that a house would survive the blaze were very limited, regardless of the trees around it.

Half of Altadena’s 28,000 trees were destroyed in the fire, and another 4,000 were removed during debris clean-up. Many of these trees had grown in the area for decades. Community members have mobilized to save Altadena’s remaining trees to maintain the town’s canopy and the benefits it provides, like habitat and shade. One of these organizations is Amigos de los Rios, a nonprofit that provides supplemental watering services to legacy trees that survived the fire. Claire Robinson, who founded the organization, says the group plans to initiate a tree-planting campaign once Altadena’s rebuilding phase is in full swing.

For Robinson, saving existing trees and cultivating native plants that survived the fire are also important, because Altadena was known for its nature. “It was so amazing to watch the mountains every day,” she says, “and have coyotes, foxes, small mammals and birds—a lot of different creatures—as part of your daily life, even though you’re in one of the biggest metro areas in the country.”

Testing native plants’ capacity to clean contaminated soil

Community Action Project LA takes a soil sample from a home in the burn area of the Eaton Fire to test for toxins at no cost to property owners. Sarah Reingewirtz / MediaNews Group / Los Angeles Daily News via Getty Images

Before Altadena rebuilds, the community needs to contend with widespread soil contamination.

Soils can be contaminated by toxins when manmade structures burn. Humans exposed to these toxic contaminants—especially vulnerable populations like children and pregnant people—can be at a risk for cancers, as well as developmental delays and other neurological impacts, according to Christine O’Connell, a soil scientist at Chapman University. Children don’t necessarily have to eat a mouthful of soil to ingest these contaminants, she explains. These soil particles are often so fine that they can unintentionally make their way onto people’s hands and faces—and into their mouths.

When the Eaton Fire burned through the community, it took with it old houses, plastics and other structures that leached lead, arsenic and PFAS chemicals into local soils. Even where structures were not burned, O’Connell says, soils were impacted by ash and smoke that drifted from other areas. That ash also contained high levels of contamination. Researchers at Caltech report the ash drifted as far as seven miles from the Eaton Fire, settling on parks and residential properties.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declined to remediate soil on a lot unless a structure burned on it. So intact homes, even those surrounded by burned structures, did not receive remediation services.

Moreover, even sites that did receive remediation in the form of “dig and dump” by the Corps—in which a layer of contaminated soil is removed and disposed of elsewhere—the Corps and the EPA didn’t perform further soil testing to see if more fire debris needed to be scraped.

Many local groups have been testing soil on properties within the L.A. fire zone. O’Connell says most data sources are estimating that between 30 and 50 percent of residential soils are testing above the recommended limits from the California Department of Toxic Substances Control. Even in properties that have been remediated by the Army Corps, the L.A. County Department of Public Health found elevated levels of lead and other toxic metals.

In addition to protecting structures against future fires, scientists think native plants could play a role in cleaning the soil impacted by the recent fires.

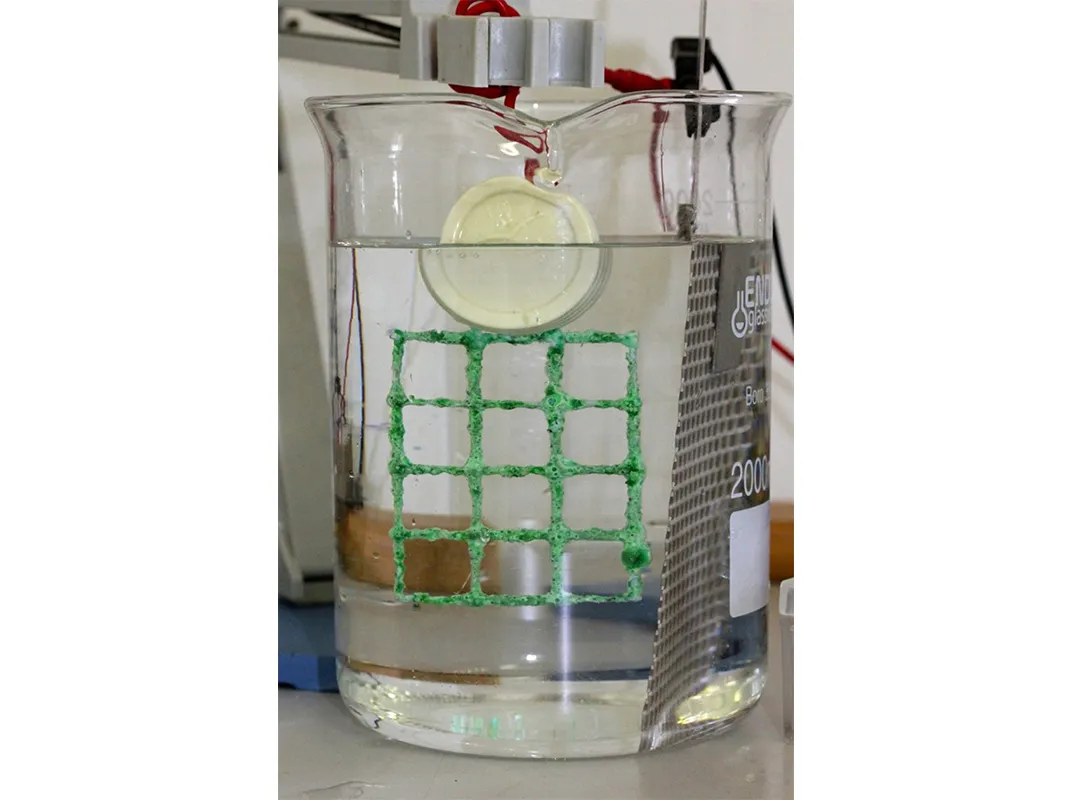

Bioremediation is the use of living organisms—plants, microbes or fungi—to detoxify contaminated environments. As plants’ root systems take in water and nutrients from the ground, they can also pull metal contaminants, like lead, from the soil and store them in the plant tissue. According to Danielle Stevenson, an environmental toxicologist at the Center for Applied Ecological Remediation, this technique offers a more ecologically and economically sustainable way to heal soils.

The dig-and-dump method, she says, is not only extremely expensive but also poses an environmental justice concern by often moving these contaminants into other people’s communities. Soil capping—another popular remediation tool that involves placing a cover, like asphalt or concrete, over contaminated soil—isn’t a great approach either, she adds, because contaminants stay in the soil and can risk leaching into the environment yet again.

Bioremediation is significantly cheaper, according to Stevenson, and done at the site. Plants that conduct bioremediation are harvested and concentrated via incineration or controlled composting to remove the contaminants they’ve collected from the environment. The metals can then be disposed of at a far smaller mass than those removed via dig-and-dump.

Stevenson, who grew up near the Cuyahoga River near Lake Erie, historically a highly polluted area, has observed the way plants and fungi are able to grow in otherwise desolate polluted sites. In the L.A. area, Stevenson has led the way in figuring out which combinations of native plants and fungi best perform bioremediation in the region. She says that native plants are especially suitable for this task, since they’re adapted to the climate of Southern California.

Mia Maltz, a mycologist at the University of Connecticut, adds that native plants are also well-adapted to local microbial communities, and the drought-tolerant deep root system of many native plants allows them to pull even more toxins from the ground. Stevenson and Maltz are both part of the SoCal Post Fire Bioremediation Coalition, a collective including scientists and advocates who are working to apply bioremediation research to public sites like schools, parks and homes.

Community members, too, are taking a lead to test native plant bioremediation. Lynn Fang, a community organizer who has worked extensively in promoting local soil health, says that elevated PFAS and lead were found in the Altadena Community Garden following the Eaton Fire. Parts of the garden have been contaminated by ash from nearby properties, and the chain-link fence that surrounds it sustained burn damage.

With the help of community volunteers, soil scientist Lauren Czaplicki and the guidance of Stevenson’s emerging research, Fang has planted squash, corn and sunflowers in what has now been designated the garden’s “remediation zone” to test these plants’ potential for removing toxins. Later, she will examine the garden’s soil quality again to see how well these plants are remediating and assess from there whether more remediation work should be done. This fall, she hopes to test more combinations of native plants for their remediation potential, with the help of donations from the Altadena Seed Library.

Looking forward, Fang hopes to cultivate new connections with scientists, conduct additional research and share more knowledge with community members about natural ways to promote the health of their soils.

In doing this, “we can kind of expand our public awareness around the different ecological tools that are available to do bioremediation,” Fang says. “People have options to do what works for them with the tools that are available and accessible.”

Amber X. Chen – AAAS Mass Media Fellow

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/d4/b5d47f35-f39c-473a-bed1-495fb3796bc0/arky3r.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/f1/50f1b2a4-6e73-4fc2-bdbe-a29078e3a740/sweethome_143.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/82/8e828d9e-7ea7-437e-a391-d6c191d2921c/sweethome_004.jpg)