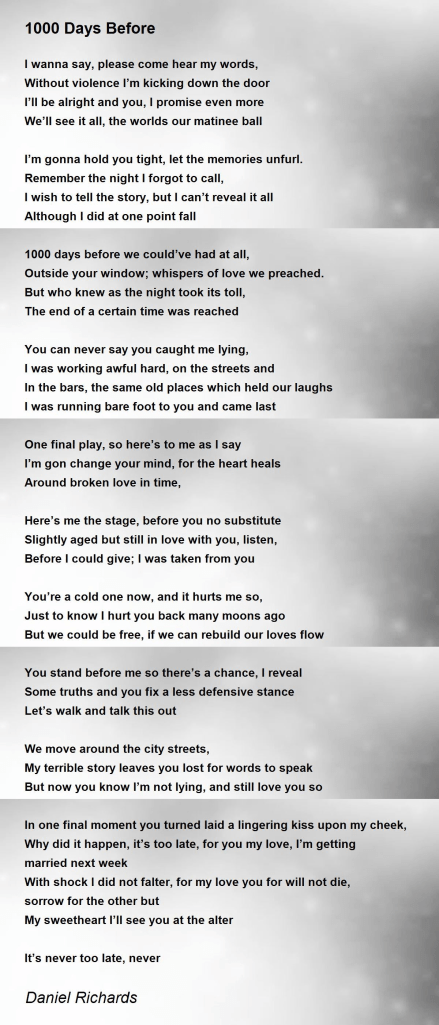

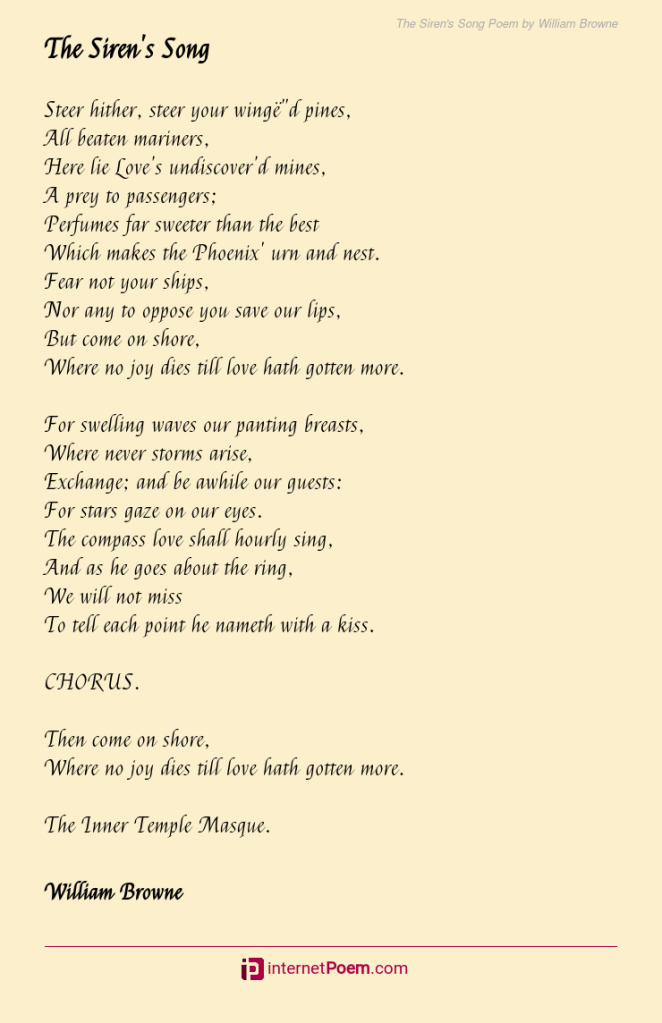

Poetry

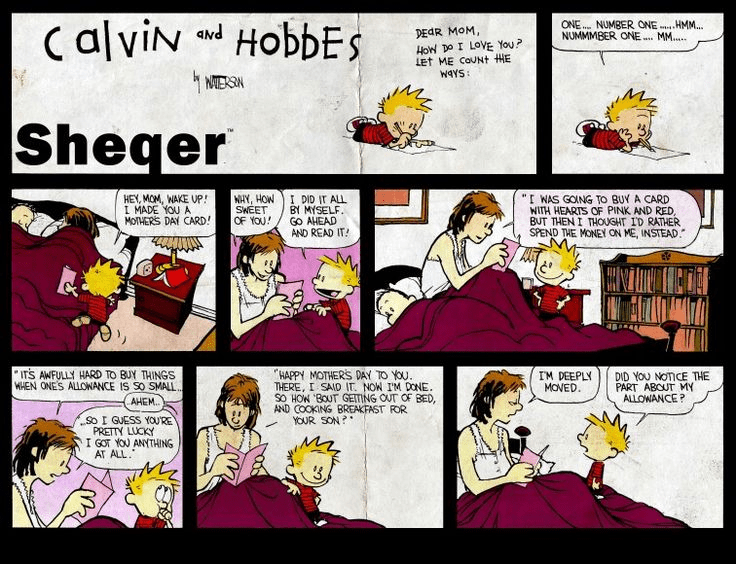

Comic Strips

Courage at the Greensboro Lunch Counter

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Object-Greensboro-Woolworth-lunch-counter-631.jpg)

On February 1, four college students sat down to request lunch service at a North Carolina Woolworth’s and ignited a struggle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

On February 1, 1960, four young African-American men, freshmen at the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina, entered the Greensboro Woolworth’s and sat down on stools that had, until that moment, been occupied exclusively by white customers. The four—Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., Joseph McNeil and David Richmond—asked to be served, and were refused. But they did not get up and leave. Indeed, they launched a protest that lasted six months and helped change America. A section of that historic counter is now held by the National Museum of American History, where the chairman of the division of politics and reform, Harry Rubenstein, calls it “a significant part of a larger collection about participation in our political system.” The story behind it is central to the epic struggle of the civil rights movement.

William Yeingst, chairman of the museum’s division of home and community life, says the Greensboro protest “inspired similar actions in the state and elsewhere in the South. What the students were confronting was not the law, but rather a cultural system that defined racial relations.”

Joseph McNeil, 67, now a retired Air Force major general living on Long Island, New York, says the idea of staging a sit-in to protest the ingrained injustice had been around awhile. “I grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina, and even in high school, we thought about doing something like that,” he recalls. After graduating, McNeil moved with his family to New York, then returned to the South to study engineering physics at the technical college in Greensboro.

On the way back to school after Christmas vacation during his freshman year, he observed the shift in his status as he traveled south by bus. “In Philadelphia,” he remembers, “I could eat anywhere in the bus station. By Maryland, that had changed.” And in the Greyhound depot in Richmond, Virginia, McNeil couldn’t buy a hot dog at a food counter reserved for whites. “I was still the same person, but I was treated differently.” Once at school, he and three of his friends decided to confront segregation. “To face this kind of experience and not challenge it meant we were part of the problem,” McNeil recalls.

The Woolworth’s itself, with marble stairs and 25,000 square feet of retail space, was one of the company’s flagship stores. The lunch counter, where diners faced rose-tinted mirrors, generated significant profits. “It really required incredible courage and sacrifice for those four students to sit down there,” Yeingst says.

News of the sit-in spread quickly, thanks in part to a photograph taken the first day by Jack Moebes of the Greensboro Record and stories in the paper by Marvin Sykes and Jo Spivey. Nonviolent demonstrations cropped up outside the store, while other protesters had a turn at the counter. Sit-ins erupted in other North Carolina cities and segregationist states.

By February 4, African-Americans, mainly students, occupied 63 of the 66 seats at the counter (waitresses sat in the remaining three). Protesters ready to assume their place crowded the aisles. After six months of diminished sales and unflattering publicity, Woolworth’s desegregated the lunch counter—an astonishing victory for nonviolent protest. “The sit-in at the Greensboro Woolworth’s was one of the early and pivotal events that inaugurated the student-led phase of the civil rights movement,” Yeingst says.

More than three decades later, in October 1993, Yeingst learned Woolworth’s was closing the Greensboro store as part of a company-wide downsizing. “I called the manager right away,” he recalls, “and my colleague Lonnie Bunch and I went down and met with African-American city council members and a group called Sit-In Movement Inc.” (Bunch is now the director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.) Woolworth’s officials agreed that a piece of the counter belonged at the Smithsonian, and volunteers from the local carpenters’ union removed an eight-foot section with four stools. “We placed the counter within sight of the flag that inspired the national anthem,” Yeingst says of the museum exhibit.

When I asked McNeil if he had returned to Woolworth’s to eat after the sit-in ended, he laughed, saying: “Well, I went back when I got to school the next September. But the food was bland, and the apple pie wasn’t that good. So it’s fair to say I didn’t go back often.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Object-Woolworth-counter-Greensboro-2.jpg)

That’s Funny

Poetry

Josephine Baker’s Memoir Is Now Being Published for the First Time in English

:focal(1050x750:1051x751)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/02/4a/024a9e1a-4226-4c3c-86a2-05307d60e306/mar2025_e06_prologue.jpg)

A newly available memoir reveals a tender, private side of the global celebrity

Kayla Randall – Digital Editor, Museums

Before she was a legend, Josephine Baker was a little girl from Missouri who loved to make funny faces. Teachers chided her for this habit; Baker paid them little heed. “Our faces aren’t made to sleep,” she later said.

Baker’s life was so full that it’s easy to imagine she never slept. Born in 1906, Baker became one of the 20th century’s biggest celebrities, known as “the Black Venus,” an enthralling dancer and singer whose career took off when she left the United States as a teenager for France, where she eventually became a citizen. She toured the globe and became the first Black woman to star in a major film, Siren of the Tropics, in 1927. During World War II, she spied for the French resistance against the Nazis. She was also a fierce fighter for civil rights in America and memorably addressed the crowd at the 1963 March on Washington.

A rare, intimate picture of Baker emerges in her memoir, Fearless and Free, originally published in France in 1949 and now translated into English for the first time. The book peels back the myth to bring readers the high-spirited child who grew up poor on Bernard Street in St. Louis, brought home lost animals and made faces in school.

An early and urgent drive, she says, was to help others: “I promised myself that when I was strong,” she said, “I would fight everyone who was mean to the poor, whether they were kings or not.”

Comic Strips

That’s Funny

Poetry