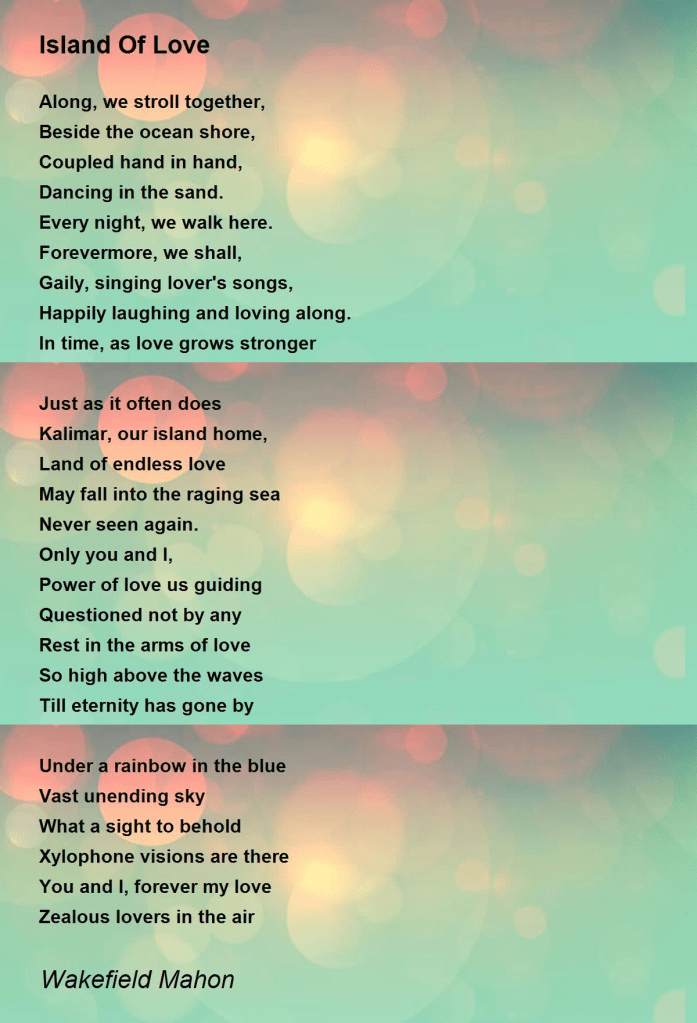

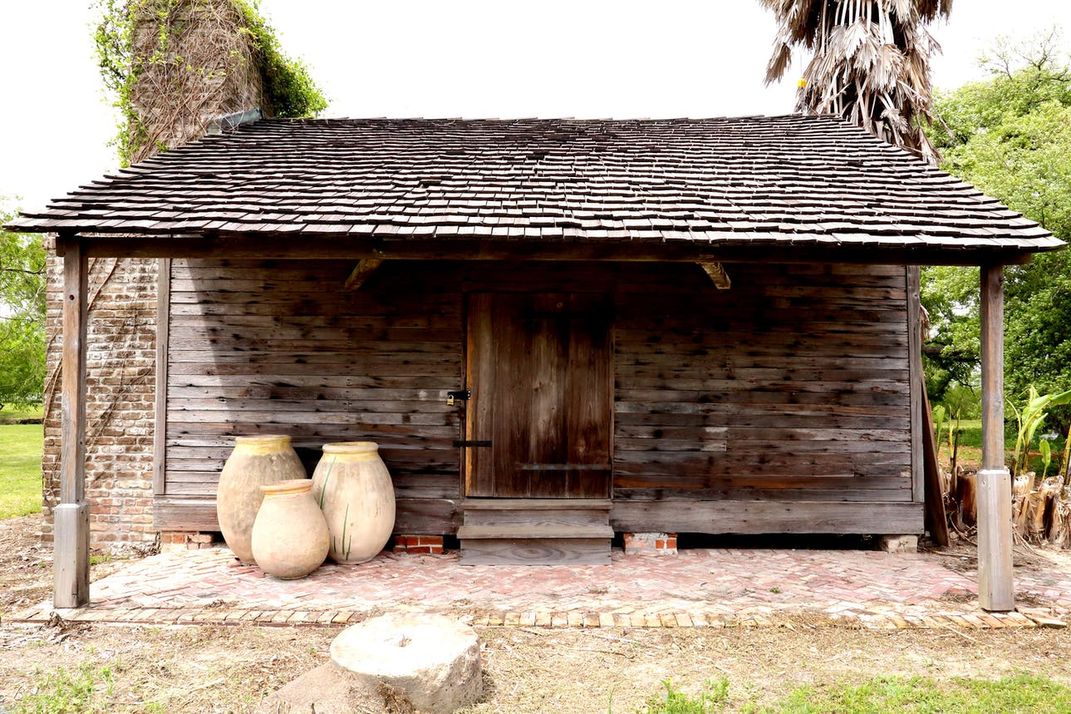

Two original slave cabins, as well as the 1790 Big House, 1790 barn and 19th-century kitchen, survived the storm. But Ida destroyed at least several structures on the historic plantation. Amber N. Mitchell / Whitney Plantation via Twitter

The historic site will remain closed indefinitely as staff assess the destruction and make repairs

Hurricane Ida’s deadly winds and downpours battered Louisiana this week, destroying buildings and knocking out power across the state. Among the sites affected by the storm was the Whitney Plantation, the state’s only museum dedicated to the lives of enslaved people.

The museum posted an update on its website announcing that it had suffered significant damage and would be closed indefinitely while staff assess the destruction and make repairs. Employees will continue to receive pay throughout the closure.

“We are still assessing damages, but it is certain that we have lost some structures,” wrote Amber N. Mitchell, the museum’s director of education, on Twitter. “Thankfully, two original slave cabins as well as the 1790 Big House, 1790 barn, and 19th-century kitchen survived.”

Arriving on the 16th anniversary of the devastating Hurricane Katrina, Ida wreaked havoc in southern Louisiana and parts of Mississippi before heading north to cause more destruction in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. As of late Thursday, about 900,000 Louisiana households were without electricity, and 185,000 had no running water, report Rebecca Santana, Melinda Deslatte and Janet McConnaughey for the Associated Press (AP).

At least 13 people in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama were reported dead due to the storm. Flooding linked to Ida also resulted in at least 46 fatalities between Maryland and Connecticut, per the AP’s Bobby Caina Calvan, David Porter and Jennifer Peltz.

Located east of New Orleans along the Mississippi River, the property was once a sugarcane plantation where enslaved people grew sugar and indigo. As of 1819, notes the museum on its website, 61 enslaved men and women lived there. Nineteen, including individuals of Mande, Bantu and Tchamba backgrounds, were born in Africa. Others were born in bondage in the Caribbean, Louisiana or other parts of the southern United States.

As Jared Keller wrote for Smithsonian magazine in 2016, a German immigrant bought the tract of land in 1752 and turned it into an indigo plantation. His descendants later made the plantation into a major player in the state’s sugar trade. (By the early 19th century, sugar had replaced indigo as Louisiana’s main cash crop.)

Today, visitors begin their tour at a historic church built on the property in 1870. Inside are clay sculptures of enslaved children “who lived and, in short order for many, died on the grounds of the plantation,” according to Smithsonian.

Artist Woodrow Nash created the statues in response to the Federal Writers’ Project, which recorded the testimonies of more than 2,300 formerly enslaved people in the late 1930s. The accounts describe brutal violence, the commonplace deaths of infants and children, and relentless backbreaking labor. Per the Whitney’s website, Nash’s sculptures “represent these former[ly enslaved people] as they were at the time of emancipation: children.”

Attorney John Cummings funded the restoration of the property, which he owned from 1999 to 2019. It opened to the public as a museum in 2014 and received more than 375,000 visitors in its first five years. In 2019, Cummings transferred ownership of the museum to a nonprofit organization governed by a board of directors. The estate stands in contrast to many other restored plantations, which frequently romanticize the lives of white landowners in the pre-Civil War South and downplay the experiences of the enslaved.

On Thursday, Clint Smith, a staff writer at the Atlantic, drew attention to the damage sustained by the plantation in a Twitter post encouraging readers to donate to help rebuild and pay staff. Smith features the museum in his bestselling book How the Word Is Passed, which recounts his visits to sites associated with slavery.

As Meilan Solly writes for Smithsonian, the book challenges common historical accounts that focus on slaveholders rather than the enslaved. Smith argues that “the history of slavery is the history of the United States, not peripheral to our founding [but] central to it.”

Livia Gershon is a daily correspondent for Smithsonian. She is also a freelance journalist based in New Hampshire. She has written for JSTOR Daily, the Daily Beast, the Boston Globe, HuffPost and Vice, among others.