Poetry, Arts, Cooking, Communication, Culture and More!

The Lawson”s

Book by MELDA BEATY

Music & Lyrics by CHARRISE BARRON

Directed by EILEEN J. MORRIS

PREVIEWS: JANUARY 22, 23 & 26

Is it possible to fall in love through a stack of letters? Bill and Audrey Lawson did. Sit-ins, arrests, and a bold move to start a church and change the landscape of Houston’s Third Ward not only threatened their lives but sealed their legacy in the Civil Rights Movement. The Lawsons is a visual history and musical journey of a time in African American history when courting was respectful, love transcended, faith superseded, and the fight for equality meant putting your life on the line for the greater good of humanity.

now on view at HMAAC | Courtesy of the artist

In the heart of the Museum District, the Houston Museum of African American Culture (HMAAC) engages visitors of every race and background with rotating art exhibitions, film screenings, tours, educational programming and more, that help explore and preserve the materials and intellectual culture of African and African Americans in Houston, the state of Texas, the southwest region, and the African Diaspora. Admission to HMAAC is always free, though donations are welcomed but not required.

Black History Month: Events That Celebrate Black Culture

These are events that energize, educate, and entertain — all while honoring and celebrating Black excellence

Virtuous Con: Black History Month February 12

Are you excited? Virtuous Con: Black History Month is this weekend!

February 12th-13th. BUY YOUR TICKETS FOR OUR VIRTUAL EVENT TODAY.

Program: 11am-6pm ET

Vendor Floor Show: 12noon – 7pm ET

Black Joy. Black Courage. Black Innovation. Black Creativity. You’ve asked for it. It’s HERE (because indie Black creators have been telling these stories for YEARS!) and yet, all too often, you still can’t find the inspiring, uplifting, fantastic stories you want.

Fortunately, there is a NEW NARRATIVE out there that is gaining force, a narrative that is inclusive, boundary-breaking, and unchained! In 2022, Virtuous Con: Black History Month is bringing these New Narrative creators straight to your living room. The BEST in cutting-edge comics, brilliant new books, and artists who challenge your ideas and your senses.

Look No Further. We’ve Got What You Need. It’s just a click away.

This February 12-13, we’re bringing you over 20 hours of programming.

Here is a preview of some of our panels. See full panel list HERE.

Luke Cage 50th Anniversary (w/ special guests David F. Walker, Cheo Hodari Coker, Aida Croal, Akela Cooper, and Evan Narcisse): The discussion will center around Luke Cage being a legacy Black comic book character introduced by white creators but “remixed” for modern audiences by Black creators and actors.

Power Center: Animation in Color (w/ special guests Peter Ramsey, Ashley Crystal Hairston, Pearl Low, Kimson Albert, Frank Abney, Jeff Trammel, and Monique Henry Hudson): From blockbuster animated films, to beloved animated television and indie projects; we’ve seen more Black talent in this space than ever before. We chat with some incredible creatives in this space who share their opinions on representation and intersectionality in animation, and the future of the tools, techniques, and opportunities in animation.

What It Takes: Getting Black Narratives to the Screen (w/ special guests Prentice Penny, Tananarive Due, Steven Barnes, Malcolm Stewart, Sebastian Jones, and Angélique Roché): It’s always great when you hear about a Black creator who is bringing their passion project to the screen or stage, but there’s often a LONG road in between. Join us as our distinguished veterans of the industry break down the real deal on what the journey entails – from concept to negotiations, to production, and more!

LGBTQ+ Contributions in Black History & Stories: Contributions by the LGBTQ+ community can be found in every corner of the globe, within every industry imaginable, but too often their presence is denied or silenced. Our incredible panelists use their own methods of communication to share stories and truths about the trailblazers and unsung heroes who pushed the movement for Black liberation and freedom for all people forward. Panelists: Doctor Jon Paul, Nick Porter, McKensie Mack, and Diamond Stylz (M)

Free Your Mind: Black Narratives in Comics: Comics and graphic novels require a very unique and specific set of story telling skills. Our panelists discuss why they chose this medium as storytellers and how they are using it to bring their most expansive visions of Black people – in the past, present, and future – to life. They will also share their take on how interactive technologies can be used to bring the comic experience to the next level. Panelists include: Jason Reeves, T.J. Sterling, Micheline Hess, Julie Anderson, Regine Sawyer, and Antonio Pomares (M)

• All access to the program panels and vendor room for both Saturday and Sunday

• A FREE download of Julie Anderson’s “A New Narrative” art work, made exclusively for Virtuous Con 2022’s Black History Month Event. (Preview cool artwork above).

• Entrance into a Grande Prize Giveaway where 2 attendees will win a gift bag with print copies of artwork, books, and comics from Stranger Comics, Otaku Noir, Rae Comics, Tuskegee Heirs, Keef Cross (Day Black Comics), Beverly Jenkins, Kwame Mbalia, Jordan Ifueko, Cerece Rennie Murphy, M.V. Media and more…tickets are $5-$10

Sat, Feb 12, 2022, 10:00 AM –

Sun, Feb 13, 2022, 6:00 PM CST

Online event

Contact the organizer to request a refund.

Eventbrite’s fee is nonrefundable.

American comedian

Clerow “Flip” Wilson Jr. was an American comedian and actor best known for his television appearances during the late 1960s and 1970s. From 1970 to 1974, Wilson hosted his own weekly variety series The Flip Wilson Show, and introduced viewers to his recurring character Geraldine. Wikipedia

Born: December 8, 1933, Jersey City, NJ

Died: November 25, 1998, Malibu, CA

Spouse: Tuanchai MacKenzie (m. 1979–1984), Lovenia Patricia Wilson (m. 1957–1967)

Children: Michelle Trice, Tamara Wilson, Stacy Wilson, Kevin Wilson, David Wilson

Parents: Clerow Wilson, Sr., Cornelia Wilson

Awards: Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Variety Series,

Pryor was the first black comedian to have major success.

Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor Sr. was an American stand-up comedian, actor, and writer. He reached a broad audience with his trenchant observations and storytelling style and is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential stand-up comedians of all time. Wikipedia

Born: December 1, 1940, Peoria, IL

Died: December 10, 2005, Encino, Los Angeles, CA

Spouse: Jennifer Lee (m. 2001–2005), MORE

Children: Richard Pryor Jr., Rain Pryor, Stephen Michael Pryor, Elizabeth Pryor, Renee Pryor, Kelsey Pryor, Franklin Pryor

Parents: LeRoy Pryor, Gertrude L. Thomas

His last film appearance was in David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997). Pryor became the first person to receive the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor from the Kennedy Center in 1998

Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor Sr. (December 1, 1940 – December 10, 2005) was an American stand-up comedian, actor, and writer. He reached a broad audience with his trenchant observations and storytelling style and is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential stand-up comedians of all time. Pryor won a Primetime Emmy Award and five Grammy Awards. He received the first Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in 1998. He won the Writers Guild of America Award in 1974. He was listed at number one on Comedy Central‘s list of all-time greatest stand-up comedians. In 2017, Rolling Stone ranked him first on its list of the 50 best stand-up comics of all time.

Pryor’s body of work includes the concert films and recordings: Richard Pryor: Live & Smokin’ (1971), That Nigger’s Crazy (1974), …Is It Something I Said? (1975), Bicentennial Nigger (1976), Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1979), Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (1982), and Richard Pryor: Here and Now (1983). As an actor, he starred mainly in comedies. His occasional roles in dramas included Paul Schrader‘s Blue Collar (1978). He also appeared in action films, like Superman III (1983). He collaborated on many projects with actor Gene Wilder, including the films Silver Streak (1976), Stir Crazy (1980), and See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989). Another frequent collaborator was actor/comedian/writer Paul Mooney.

photo of Pryor for one of his Mister Kelly’s appearances, 1968–1969

In 1963, Pryor moved to New York City and began performing regularly in clubs alongside performers such as Bob Dylan and Woody Allen. On one of his first nights, he opened for singer and pianist Nina Simone at New York’s Village Gate. Simone recalls Pryor’s bout of performance anxiety:

He shook like he had malaria, he was so nervous. I couldn’t bear to watch him shiver, so I put my arms around him there in the dark and rocked him like a baby until he calmed down. The next night was the same, and the next, and I rocked him each time.

Inspired by Bill Cosby, Pryor began as a middlebrow comic, with material far less controversial than what was to come. Soon, he began appearing regularly on television variety shows, such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Merv Griffin Show, and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. His popularity led to success as a comic in Las Vegas. The first five tracks on the 2005 compilation CD Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966–1974), recorded in 1966 and 1967, capture Pryor in this period.

In September 1967, Pryor had what he described in his autobiography Pryor Convictions (1995) as an “epiphany“. He walked onto the stage at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas (with Dean Martin in the audience), looked at the sold-out crowd, exclaimed over the microphone, “What the fuck am I doing here!?”, and walked off the stage. Afterward, Pryor began working profanity into his act, including the word nigger. His first comedy recording, the eponymous 1968 debut release on the Dove/Reprise label, captures this particular period, tracking the evolution of Pryor’s routine. Around this time, his parents died—his mother in 1967 and his father in 1968.

In 1969, Pryor moved to Berkeley, California, where he immersed himself in the counterculture and rubbed elbows with the likes of Huey P. Newton and Ishmael Reed.

Pryor performed in the Lily Tomlin specials. He is seen here with Tomlin and Alan Alda in Tomlin’s 1973 special.

In the 1970s, Pryor wrote for television shows such as Sanford and Son, The Flip Wilson Show, and a 1973 Lily Tomlin special, for which he shared an Emmy Award. During this period, Pryor tried to break into mainstream television. He also appeared in several popular films, including Lady Sings the Blues (1972), The Mack (1973), Uptown Saturday Night (1974), Silver Streak (1976), Car Wash (1976), Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings (1976), Which Way Is Up? (1977), Greased Lightning (1977), Blue Collar (1978), and The Muppet Movie (1979).

Pryor signed with the comedy-oriented independent record label Laff Records in 1970, and in 1971 recorded his second album, Craps (After Hours). Two years later, the relatively unknown comedian appeared in the documentary Wattstax (1972), wherein he riffed on the tragic-comic absurdities of race relations in Watts and the nation. Not long afterward, Pryor sought a deal with a larger label, and he signed with Stax Records in 1973. When his third, breakthrough album, That Nigger’s Crazy (1974), was released, Laff, which claimed ownership of Pryor’s recording rights, almost succeeded in getting an injunction to prevent the album from being sold. Negotiations led to Pryor’s release from his Laff contract. In return for this concession, Laff was enabled to release previously unissued material, recorded between 1968 and 1973, at will. That Nigger’s Crazy was a commercial and critical success; it was eventually certified gold by the RIAA and won the Grammy Award for Best Comedy Album at the 1975 Grammy Awards.

Grammy Awards

the legal battle, Stax briefly closed its doors. At this time, Pryor returned to Reprise/Warner Bros. Records, which re-released That Nigger’s Crazy, immediately after …Is It Something I Said?, his first album with his new label. Like That Nigger’s Crazy, the album was a hit with both critics and fans; it was eventually certified platinum by the RIAA and won the Grammy Award for Best Comedy Recording at the 1976 Grammy Awards.

Pryor’s 1976 release Bicentennial Nigger continued his streak of success. It became his third consecutive gold album, and he collected his third consecutive Grammy for Best Comedy Recording for the album in 1977. With every successful album Pryor recorded for Warner (or later, his concert films and his 1980 freebasing accident), Laff quickly published an album of older material to capitalize on Pryor’s growing fame—a practice they continued until 1983. The covers of Laff albums tied in thematically with Pryor movies, such as Are You Serious? for Silver Streak (1976), The Wizard of Comedy for his appearance in The Wiz (1978), and Insane for Stir Crazy (1980).

Pryor co-wrote Blazing Saddles (1974), directed by Mel Brooks and starring Gene Wilder. Pryor was to play the lead role of Bart, but the film’s production studio would not insure him, and Mel Brooks chose Cleavon Little, instead.

In 1975, Pryor was a guest host on the first season of Saturday Night Live and the first black person to host the show. Pryor’s longtime girlfriend, actress and talk-show host Kathrine McKee (sister of Lonette McKee), made a brief guest appearance with Pryor on SNL. Among the highlights of the night was the now-controversial “word association” skit with Chevy Chase. He would later do his own variety show, The Richard Pryor Show, which premiered on NBC in 1977. The show was cancelled after only four episodes probably because television audiences did not respond well to his show’s controversial subject matter, and Pryor was unwilling to alter his material for network censors. ‘They offered me ten episodes, but I said all I wanted to in four’. During the short-lived series, he portrayed the first black President of the United States, spoofed the Star Wars Mos Eisley cantina, examined gun violence in a non-comedy skit, lampooned racism on the sinking Titanic and even used costumes and visual distortion to appear nude.

In 1979, at the height of his success, Pryor visited Africa. Upon returning to the United States, Pryor swore he would never use the word “nigger” in his stand-up comedy routine again

1980’s

on a freebasing binge during the making of the film Stir Crazy (1980), Pryor doused himself in rum and set himself on fire. Pryor incorporated a description of the incident into his comedy show Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (1982). He joked that the event was caused by dunking a cookie into a glass of low-fat and pasteurized milk, causing an explosion. At the end of the bit, he poked fun at people who told jokes about it by waving a lit match and saying, “What’s that? Richard Pryor running down the street.”

Before his horribly damaging 1980 freebasing incident, Pryor was about to start filming Mel Brooks’ History of the World, Part I (1981), but was replaced at the last minute by Gregory Hines. Likewise, Pryor was scheduled for an appearance on The Muppet Show at that time, which forced the producers to cast their British writer, Chris Langham, as the guest star for that episode instead.

After his “final performance”, Pryor did not stay away from stand-up comedy for long. Within a year, he filmed and released a new concert film and accompanying album, Richard Pryor: Here and Now (1983), which he directed himself. He also wrote and directed a fictionalized account of his life, Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling, which revolved around the 1980 freebasing incident.

In 1983 Pryor signed a five-year contract with Columbia Pictures for $40 million and he started his own production company, Indigo Productions. Softer, more formulaic films followed, including Superman III (1983), which earned Pryor $4 million; Brewster’s Millions (1985), Moving (1988), and See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989). The only film project from this period that recalled his rough roots was Pryor’s semiautobiographic debut as a writer-director, Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling, which was not a major success.

Pryor was also originally considered for the role of Billy Ray Valentine on Trading Places (1983), before Eddie Murphy won the part.[citation needed]

Despite his reputation for constantly using profanity on and off camera, Pryor briefly hosted a children’s show on CBS called Pryor’s Place (1984). Like Sesame Street, Pryor’s Place featured a cast of puppets (animated by Sid and Marty Krofft), hanging out and having fun in a friendly inner-city environment along with several children and characters portrayed by Pryor himself. Its theme song was performed by Ray Parker, Jr. However, Pryor’s Place frequently dealt with more sobering issues than Sesame Street. It was cancelled shortly after its debut.

Pryor co-hosted the Academy Awards twice and was nominated for an Emmy for a guest role on the television series Chicago Hope. Network censors had warned Pryor about his profanity for the Academy Awards, and after a slip early in the program, a five-second delay was instituted when returning from a commercial break. Pryor is also one of only three Saturday Night Live hosts to be subjected to a rare five-second delay for his 1975 appearance (along with Sam Kinison in 1986 and Andrew Dice Clay in 1990).

Pryor developed a reputation for being demanding and disrespectful on film sets, and for making selfish and difficult requests. In his autobiography Kiss Me Like a Stranger, co-star Gene Wilder says that Pryor was frequently late to the set during filming of Stir Crazy, and that he demanded, among other things, a helicopter to fly him to and from set because he was the star. Pryor was also accused of using allegations of on-set racism to force the hand of film producers into giving him more money:

One day during our lunch hour in the last week of filming, the craft service man handed out slices of watermelon to each of us. Richard, the whole camera crew, and I sat together in a big sound studio eating a number of watermelon slices, talking and joking. As a gag, some members of the crew used a piece of watermelon as a Frisbee, and tossed it back and forth to each other. One piece of watermelon landed at Richard’s feet. He got up and went home. Filming stopped. The next day, Richard announced that he knew very well what the significance of watermelon was. He said that he was quitting show business and would not return to this film. The day after that, Richard walked in, all smiles. I wasn’t privy to all the negotiations that went on between Columbia and Richard’s lawyers, but the camera operator who had thrown that errant piece of watermelon had been fired that day. I assume now that Richard was using drugs during Stir Crazy.

Pryor appeared in Harlem Nights (1989), a comedy-drama crime film starring three generations of black comedians (Pryor, Eddie Murphy, and Redd Foxx).

1990s-2000s

In his later years starting in the early to mid-1990s, Pryor used a power-operated mobility scooter due to multiple sclerosis (MS). To him, MS stood for “More Shit”. He appears on the scooter in his last film appearance, a small role in David Lynch‘s Lost Highway (1997) playing an auto-repair garage manager named Arnie.

Rhino Records remastered all of Pryor’s Reprise and WB albums for inclusion in the box set … And It’s Deep Too! The Complete Warner Bros. Recordings (1968–1992) (2000).

In late December 1999, Pryor appeared in the cold open of The Norm Show in the episode entitled “Norm vs. The Boxer”. He played Mr. Johnson, an elderly man in a wheelchair who has lost the rights to in-home nursing when he kept attacking the nurses before attacking Norm himself. This was his last television appearance.

In 2002, Pryor and Jennifer Lee Pryor, his wife and manager, won legal rights to all the Laff material, which amounted to almost 40 hours of reel-to-reel analog tape. After going through the tapes and getting Richard’s blessing, Jennifer Lee Pryor gave Rhino Records access to the tapes in 2004. These tapes, including the entire Craps (After Hours) album, form the basis of the February 1, 2005, double-CD release Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966–1974)

Richard Pryor’s star at the Hollywood Walk of Fame, covered with items left by fans

Jerry Seinfeld called Pryor “the Picasso of our profession” and Bob Newhart heralded Pryor as “the seminal comedian of the last 50 years.” Dave Chappelle said of Pryor, “You know those, like, evolution charts of man? He was the dude walking upright. Richard was the highest evolution of comedy.” This legacy can be attributed, in part, to the unusual degree of intimacy Pryor brought to bear on his comedy. As Bill Cosby reportedly once said, “Richard Pryor drew the line between comedy and tragedy as thin as one could possibly paint it.”

Main article: List of awards and nominations received by Richard Pryor

In 1998, Pryor won the first Mark Twain Prize for American Humor from the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. According to former Kennedy Center President Lawrence J. Wilker, Pryor was selected as the first recipient of the Prize because:

as a stand-up comic, writer, and actor, he struck a chord, and a nerve, with America, forcing it to look at large social questions of race and the more tragicomic aspects of the human condition. Though uncompromising in his wit, Pryor, like Twain, projects a generosity of spirit that unites us. They were both trenchant social critics who spoke the truth, however outrageous.

In 2004, Pryor was voted number one on Comedy Central‘s list of the 100 Greatest Stand-ups of All Time. In a 2005 British poll to find “The Comedian’s Comedian,” Pryor was voted the 10th-greatest comedy act ever by fellow comedians and comedy insiders.

Preston Jackson’s Pryor in Peoria, Illinois

Pryor was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006.

The animal rights organization PETA gives out an award in Pryor’s name to people who have done outstanding work to alleviate animal suffering. Pryor was active in animal rights and was deeply concerned about the plight of elephants in circuses and zoos. In 1999, he was awarded a Humanitarian Award by the group, and worked with them on campaigns against the treatment of birds by KFC.

Artist Preston Jackson created a life-sized bronze statue in dedication to the beloved comedian and named it Richard Pryor: More than Just a Comedian. It was placed at the corner of State and Washington Streets in downtown Peoria, on May 1, 2015, close to the neighborhood in which he grew up with his mother. The unveiling was held Sunday, May 3, 2015

In 2002, a television documentary entitled The Funny Life of Richard Pryor depicted Pryor’s life and career. Broadcast in the UK as part of the Channel 4 series Kings of Black Comedy, it was produced, directed and narrated by David Upshal and featured rare clips from Pryor’s 1960s stand-up appearances and films such as Silver Streak (1976), Blue Collar (1978), Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1978), and Stir Crazy (1980). Contributors included George Carlin, Dave Chappelle, Whoopi Goldberg, Ice-T, Paul Mooney, Joan Rivers, and Lily Tomlin. The show tracked down the two cops who had rescued Pryor from his “freebasing incident”, former managers, and even school friends from Pryor’s home town of Peoria, Illinois. In the US, the show went out as part of the Heroes of Black Comedy series on Comedy Central, narrated by Don Cheadle.

A television documentary, Richard Pryor: I Ain’t Dead Yet, #*%$#@!! (2003) consisted of archival footage of Pryor’s performances and testimonials from fellow comedians, including Dave Chappelle, Denis Leary, Chris Rock, and Wanda Sykes, on Pryor’s influence on comedy.

On December 19, 2005, BET aired a Pryor special, titled The Funniest Man Dead or Alive. It included commentary from fellow comedians, and insight into his upbringing.

A retrospective of Pryor’s film work, concentrating on the 1970s, titled A Pryor Engagement, opened at Brooklyn Academy of Music Cinemas for a two-week run in February 2013. Several prolific comedians who have claimed Pryor as an influence include George Carlin, Dave Attell, Martin Lawrence, Dave Chappelle, Chris Rock, Colin Quinn, Patrice O’Neal, Bill Hicks, Jerry Seinfeld, Jon Stewart, Bill Burr, Joey Diaz, Eddie Murphy, Louis C.K., and Eddie Izzard.

On May 31, 2013, Showtime debuted the documentary Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic directed by Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Marina Zenovich. The executive producers were Pryor’s widow Jennifer Lee Pryor and Roy Ackerman. Interviewees included Dave Chappelle, Whoopi Goldberg, Jesse Jackson, Quincy Jones, George Lopez, Bob Newhart, Richard Pryor, Jr., Lily Tomlin, and Robin Williams.

On March 12, 2019, Paramount Network debuted the documentary I Am Richard Pryor, directed by Jesse James Miller. The film included appearances by Sandra Bernhard, Lily Tomlin, Mike Epps, Howie Mandel, and Pryor’s ex-wife, Jennifer Lee Pryor, among others. Jennifer Lee also served as an executive producer on the film.

In the episode “Taxes and Death or Get Him to the Sunset Strip” (2012), the voice of Richard Pryor is played by Eddie Griffin in the satirical TV show Black Dynamite.

A planned biopic, entitled Richard Pryor: Is It Something I Said?, was being produced by Chris Rock and Adam Sandler. The film would have starred Marlon Wayans as the young Pryor.Other actors previously attached include Mike Epps and Eddie Murphy. The film would have been directed by Bill Condon and was still in development with no release date, as of February 2013.

The biopic remained in limbo, and went through several producers until it was announced in January 2014 that it was being backed by The Weinstein Company with Lee Daniels as director. It was further announced, in August 2014, that the biopic will have Oprah Winfrey as producer and will star Mike Epps as Pryor.

He is portrayed by Brandon Ford Green in Season 1 Episode 4 “Sugar and Spice” of Showtime‘s I’m Dying Up Here.

In the Epic Rap Battles of History episode George Carlin vs. Richard Pryor, Pryor was portrayed by American rapper ZEALE

Pryor met actress Pam Grier through comedian Freddie Prinze. They began dating when they were both cast in Greased Lightning (1977). Grier helped Pryor learn to read and tried to help him with his drug addiction. Pryor married another woman while dating Grier.

Pryor dated actress Margot Kidder during the filming of Some Kind of Hero (1982). Kidder stated that she “fell in love with Pryor in two seconds flat” after they first met.

Pryor was married seven times to five women:

Pryor had seven children with six different women:

Nine years after Pryor’s death, in 2014 the biographical book Becoming Richard Pryor by Scott Saul stated that Pryor “acknowledged his bisexuality” and in 2018, Quincy Jones and Pryor’s widow Jennifer Lee claimed that Pryor had had a sexual relationship with Marlon Brando, and that Pryor was open about his bisexuality with his friends. Pryor’s daughter Rain later disputed the claim, to which Lee stated that Rain was in denial about her father’s bisexuality. Lee later told TMZ, in explanation, that “it was the 70s! Drugs were still good… If you did enough cocaine, you’d fuck a radiator and send it flowers in the morning”. In his autobiography Pryor Convictions, Pryor talked about having a two-week relationship with Mitrasha, a trans woman, which he called “two weeks of being gay.” In his first special, Live & Smokin’, Pryor discusses performing fellatio, and in 1977, he said at a gay rights show at the Hollywood Bowl, “I have sucked a dick.”

Late in the evening of June 9, 1980, Pryor poured 151-proof rum all over himself and lit himself on fire. The Los Angeles police reported he was burned by an explosion while freebasing cocaine. Pryor claimed his injuries were caused by burning rum. While ablaze, he ran down Parthenia Street from his Los Angeles home, until being subdued by police. He was taken to a hospital, where he was treated for second- and third-degree burns covering more than half of his body. Pryor spent six weeks in recovery at the Grossman Burn Center at Sherman Oaks Hospital. His daughter Rain stated that the incident happened as a result of a bout of drug-induced psychosis.

Pryor’s widow Jennifer Lee recalled when he began freebasing cocaine: “After two weeks of watching him getting addicted to this stuff I moved out. It was clear the drug had moved in and it had become his lover and everything. I did not exist.”

In November 1977, after many years of heavy smoking and drinking, Pryor suffered a mild heart attack at age 37. He recovered and resumed performing in January the following year. In 1986, he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. In 1990, Pryor suffered a second heart attack while in Australia. He underwent triple heart bypass surgery in 1991.

In late 2004, his sister said he had lost his voice as a result of his multiple sclerosis. However, on January 9, 2005, Pryor’s wife, Jennifer Lee, rebutted this statement in a post on Pryor’s official website, citing Richard as saying: “I’m sick of hearing this shit about me not talking … not true … I have good days, bad days … but I still am a talkin’ motherfucker!”

On December 10, 2005, nine days after his 65th birthday, Pryor suffered a third heart attack in Los Angeles. He was taken to a local hospital after his wife’s attempts to resuscitate him failed. He was pronounced dead at 7:58 a.m. PST. His widow Jennifer was quoted as saying, “At the end, there was a smile on his face.” He was cremated, and his ashes were given to his family. His ashes were later scattered in the bay at Hana, Hawaii by his widow in 2019. Forensic pathologist Michael Hunter believes Pryor’s fatal heart attack was caused by coronary artery disease that was at least partially brought about by years of tobacco smoking

| Year | Title | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Richard Pryor | Dove/Reprise Records | |

| 1971 | Craps (After Hours) | Laff Records | Reissued 1993 by Loose Cannon/Island |

| 1974 | That Nigger’s Crazy | Partee/Stax | Reissued 1975 by Reprise Records |

| 1975 | …Is It Something I Said? | Reprise Records | Reissued 1991 on CD by Warner Bros. Records |

| 1976 | Are You Serious ??? | Laff Records | |

| 1976 | Rev. Du Rite | Laff Records | |

| 1976 | Holy Smoke! | Laff Records | |

| 1976 | Bicentennial Nigger | Warner Bros. Records | Reissued 1989 on CD by Warner Bros. Records |

| 1976 | Insane | Laff Records | |

| 1976 | L.A. Jail | Tiger Lily Records | |

| 1977 | Who Me? I’m Not Him | Laff Records | |

| 1977 | Richard Pryor Live | World Sound Records | |

| 1978 | The Wizard of Comedy | Laff Records | |

| 1978 | Black Ben The Blacksmith | Laff Records | |

| 1978 | Wanted: Live in Concert | Warner Bros. Records | Double–LP set |

| 1979 | Outrageous | Laff Records | |

| 1982 | Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip | Warner Bros. Records | |

| 1982 | Supernigger | Laff Records | |

| 1983 | Richard Pryor: Here and Now | Warner Bros. Records | |

| 1983 | Richard Pryor Live! | Phoenix/Audiofidelity | Picture disc |

| 1983 | Blackjack | Laff Records |

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | The Busy Body | Lt. Whitaker | Film debut |

| 1968 | Wild in the Streets | Stanley X | |

| 1969 | Uncle Tom’s Fairy Tales | Unknown | Also producer and writer; uncompleted/unreleased |

| 1970 | Carter’s Army | Pvt. Jonathan Crunk | |

| 1970 | The Phynx | Richard Pryor (cameo) | |

| 1971 | You’ve Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You’ll Lose That Beat | Wino | |

| 1971 | Live & Smokin’ | Richard Pryor | Stand-up film; also writer |

| 1971 | Dynamite Chicken | Richard Pryor | |

| 1972 | Lady Sings the Blues | Piano Man | |

| 1973 | The Mack | Slim | |

| 1973 | Some Call It Loving | Jeff | |

| 1973 | Hit! | Mike Willmer | |

| 1973 | Wattstax | Richard Pryor / Host | |

| 1974 | Uptown Saturday Night | Sharp Eye Washington | |

| 1975 | Adiós Amigo | Sam Spade | |

| 1976 | The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings | Charlie Snow, All-Star (RF) | |

| 1976 | Car Wash | Daddy Rich | |

| 1976 | Silver Streak | Grover T. Muldoon | |

| 1977 | Greased Lightning | Wendell Scott | |

| 1977 | Which Way Is Up? | Leroy Jones / Rufus Jones / Reverend Lenox Thomas | |

| 1978 | Blue Collar | Zeke Brown | |

| 1978 | The Wiz | Herman Smith (The Wiz) | |

| 1978 | California Suite | Dr. Chauncey Gump | |

| 1979 | Richard Pryor: Live in Concert | Richard Pryor | Stand-up film; also writer |

| 1979 | The Muppet Movie | Balloon Vendor (cameo) | |

| 1980 | Wholly Moses! | Pharaoh | |

| 1980 | In God We Tru$t | G.O.D. | |

| 1980 | Stir Crazy | Harold “Harry” Monroe | |

| 1981 | Bustin’ Loose | Joe Braxton | Also producer and writer (story) |

| 1982 | Some Kind of Hero | Eddie Keller | |

| 1982 | Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip | Richard Pryor | Stand-up film; also producer and writer |

| 1982 | The Toy | Jack Brown | |

| 1983 | Superman III | August “Gus” Gorman | |

| 1983 | Richard Pryor: Here and Now | Richard Pryor | Stand-up film; also director and writer |

| 1985 | Brewster’s Millions | Montgomery Brewster | |

| 1986 | Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling | Jo Jo Dancer | Also director, producer and writer |

| 1987 | Critical Condition | Kevin Lenahan / Dr. Eddie Slattery | |

| 1988 | Moving | Arlo Pear | |

| 1989 | See No Evil, Hear No Evil | Wallace “Wally” Karue | |

| 1989 | Harlem Nights | Sugar Ray | |

| 1991 | Another You | Eddie Dash | |

| 1991 | The Three Muscatels | Narrator / Wino / Bartender | |

| 1996 | Mad Dog Time | Jimmy the Grave Digger | |

| 1997 | Lost Highway | Arnie | Final film role |

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | The Wild Wild West | Villar | Episode: “The Night of the Eccentrics” |

| 1967 | ABC Stage 67 | Undertaker | Episode: “A Time for Laughter: A Look at Negro Humor in America” |

| 1968 | Let’s Go | Unknown role | Episode: “Psychedelic Vancouver” |

| 1969 | The Young Lawyers | Otis Tucker | Episode: “The Young Lawyers” |

| 1971 | The Partridge Family | A.E. Simon | Episode: “Soul Club” |

| 1972 | Mod Squad | Cat Griffin | Episode: “The Connection” |

| 1975 | Saturday Night Live | Himself/Host | Episode: “Richard pryor/Gil Scott-Heron“ |

| 1977 | The Richard Pryor Special? | Himself / The Reverend James L. White / Idi Amin Dada / Shoeshine Man / Willie | TV special |

| 1977 | The Richard Pryor Show | Himself / Various roles | 4 episodes |

| 1975-1978 | Sesame Street | Himself | 4 episodes |

| 1984 | Pryor’s Place | Himself | 10 episodes |

| 1984 | Billy Joel: Keeping the Faith | Man Reading Newspaper | Video short |

| 1993 | Martin | Himself | Episode: “The Break Up: Part 1” |

| 1995 | Chicago Hope | Joe Springer | Episode: “Stand” |

| 1996 | Malcolm & Eddie | Uncle Bucky | Episode: “Do the K.C. Hustle” |

| 1999 | The Norm Show | Mr. Johnson | Episode: “Norm vs. the Boxer” |

Oscar Micheaux

Just four years after the release of Birth of a Nation, a film so popular in America that it was shown at the White House in 1915, Oscar Micheaux entered the industry, releasing his debut film The Homesteader as the first major black feature filmmaker

“There is no barrier to success which diligence and perseverance cannot hurdle.” – Oscar Micheaux

In the infancy of the 20th century, cinema remained an exclusive form of art, reserved only for those who could source and afford the rudimentary yet expensive equipment necessary to create a feature film. Taken up as a source of experimentation by confident emerging artists as well as ambitious feature filmmakers, early cinema was dominated by the loudest voices, with 1915’s Birth of a Nation reflecting the racism that remained stagnant in America ever since The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

Just four years after the release of Birth of a Nation, a film so popular in America that it was shown at the White House in 1915, Oscar Micheaux entered the industry, releasing his debut film The Homesteader as the first major black feature filmmaker. Defying the makeup of the contemporary industry that consisted only of white male filmmakers, Micheaux pioneered black cinema with dogged perseverance, telling stories that conveyed the hardship of the black experience whilst challenging the damaging cultural norms that had become ingrained in American society.

Demonstrating such tenacity from a young age, Oscar Micheaux moved to Chicago at the age of 17 at the wish of his father, where he pursued a career in business, setting up his own shoeshine stand before becoming a Pullman porter on the railroads. Through the nature of this state-hopping job, Micheaux was lucky enough to travel across the United States from a young age, save up a considerable amount of money and meet several wealthy individuals who would become imperative in bolstering his future career.

Armed with a wealth of knowledge and an impressive amount of social skills, Micheaux moved to Gregory County, South Dakota, where he worked as a homesteader, living out the reality that would later inspire several of his films and stories. Soon deciding to focus his career on an entirely new industry, Oscar Micheaux set out on becoming an author, subsequently writing several novels by the middle of the 20th century.

Printing 1000 copies of his first book The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer in 1913, Micheaux based his story on his time as a homesteader along with the failures of his first marriage with Orlean McCracken. Fuelled by a passionate theme that asked the black population of the USA to realise their potential and strive to succeed in areas they previously had not, Micheaux became a pioneering voice for the black community. Five years later, following the release of his novel The Homesteader, Micheaux decided to found the Micheaux Film & Book Company of Sioux City in Chicago and turn his novel into a feature film after turning down initial interest from a producer in Los Angeles.

Contacting the wealthy clients he had come across during his time as a porter for financial interest, Micheaux hired actors and secured a filming location for his very first, historic feature film. Revolving around a man named Jean Baptiste who falls in love with several white women only to resist his urges and marry a black woman instead, the film becomes a complicated web of moral turbulence as Oscar Micheaux juggles issues of race relationships and tries to find a solution to the quandary.

During a time of significant social and political change in America, the films of Micheaux dealt with the realities and challenges of living as a black man in America, often offering intellectual responses to cultural statements of intent such as D. W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation. Considered Micheaux’s answer to Griffiths’ film, Within Our Gates was released in 1920 and contrasts the experiences of black people who had stayed in the rural country with those who had been urbanised by the cities. Exploring the suffering of black men, women and children in contemporary America, the film was considered to be pivotal in bringing the injustices of black people to the consciousnesses of the white American people.

Opposing, breaking down and discussing the racial injustices that black Americans faced on a regular basis including discrimination, mob violence, lynching and more, Micheaux’s mission was to provide a counterpoint of representation to the racist stereotypes the likes of D. W. Griffith offered in popular cinema. In pursuit of this, he created complex, wise and emotionally intelligent characters that presented black people in a light that had never been publicly portrayed. As Micheaux, himself stated, “It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights”.

As a result of Oscar Micheaux’s own remarkable resilience, black American cinema is now thriving, and continues, in his own vein, to challenge prejudice and provide an all-encompassing view of the black experience.

Watch Oscar Micheaux’s iconic film Within Our Gates for free in its entirety, below.

Daryl Ladalle Shular, certified chef d’cuisine (CCC), was born on September 10, 1973, in Winter Haven, Florida, to Nevada Tungstall Robinson and Thomas Lee Shular. He attended Central Elementary School, Stambough Middle School where he played sports, and Auburndale High School where he graduated in 1992. His classmates included pro basketball player Tracy McGrady. Shular earned his A.A. degree in culinary arts from The Art Institute of Atlanta (AIA), where he learned the difference between being a chef and a cook.

Shular worked as a sous chef at Atlanta’s Anthony’s Restaurant from 1993 to 1994; executive sous chef at the Buckhead Club from 1994 to 1995; executive chef at the Doubletree Hotel from 1998 to 2000; and as chef d’cuisine at Spice Restaurant in 2001. He also served as banquet chef at Villa Christina. Since 2001, Shular has been a mainstay of the AIA faculty, where he teaches culinary arts. A member of the American Culinary Federation (ACF) and the National Association of Catering Executives, Shular is an ACF certified chef de cuisine. He is also a member of the World Culinary Association’s Atlanta chapter. The young chef has won more than a dozen culinary competitions including the gold medal at the 2004 Southeast Restaurant Hotel, Motel Show; the gold medal first place award Signature Meal at the Sysco Culinary Salon in 2004; the ACF Nutritional Hot Food Challenge at the Orlando World Marriot in 2004; and the NAEM Invitational Culinary Salon gold medal in 2003. Shular is a three time champion of the Sysco Culinary Competition.

One of the most respected young chefs in the country, Shular is on the board of directors of Pecan Restaurant and Onyx Restaurant, both in Atlanta. Shular was selected to join the United States 2008 Culinary Olympic Team. His goal is to become the first African American to attain the status of Master Chef from the ACI in 2009.

Shular lives with his wife and two children in Atlanta.

How old are your children today?

Marlena: My son is 16 and my daughter is 12.

For you, what was your surroundings like when you were pregnant with your first child knowing he was half African American?

Marlena: My surroundings were complicated. I was in my first apartment on my own. The father was there but wasn’t there. I had the support of my grandmother and my mother completely.

Looking back how does the fears for him differ if any from then to the environment we’re in now?

Marlena: My fears are very different from when he was born. The environment has changed so much over the years. Things are so much more in focus than ever. This world has made some great changes. The world has a lot of incidents that shouldn’t have happened but it brought a better light to some issues that needed to seen. I have had talks with my son about these issues

Do you see people treating your child as a statistic & if so how do you handle it for him to understand?

Marlena: Yes I do see people treating my child as a statistic. I have talked to him about how people can see them and how they see themselves. I always tell them to “always be their self no matter what” I also tell him to embrace both of his races.

When Black Lives Matter started what was your first thoughts?

Marlena: I loved the fact Black Lives Matter started. I was glad to see the changes being made. It still is a work in process. I will always support this movement even if I didn’t have biracial children. I have always seen people as people not as their race. I have also taught my kids to “never see color but a person for who they are”

What are your fears for your children?

Marlena: My fear for both my kids is that they won’t be able to pick themselves up after any major downfall or issue especially when it comes to them being biracial. . Even tho I have helped them figure out their own ways. My children have been taught to embrace both of their races. If they believe something doesn’t feel right, we have discussions about how they feel about it.

when you had your 2nd child what were your worries knowing it was a girl?

Marlena: Only fear I have is that my daughter will have an attitude that is worst than mine. Also, she will not be able to control it to better herself. Her generation is way worse than my generation growing up.

How do you help her cope with the reality she will be judged because she is mixed by other females?

Marlena: I talk to her every day about different topics. I have even sung a song to her that helps her. The song I sing to her is Body in Motion. At the end of the song where it says” Baby, you’re gorgeous, You’re incredible, You’re beautiful, You’re phenomenal, You’re amazin’, Most importantly, you’re a queen”. She just smiles and laughs when i do that. It makes her feel so much better.

How do you guide your children as they grow into their personalities when they are in situations that they have to be cautious of because of their skin tone?

Marlena: I talk to them about any situation that comes up. Also how their personality could make for a better or worse situation. My children have too completely personalities. One is quiet and one is loud. I have to explain to them in very different ways.

What do you want your children to understand about the world that they fully haven’t experienced yet?

Marlena: That this world is forever changing. Don’t expect things to always work. Don’t expect people to always have your best interests at heart.

Raising a young man is difficult specially alone without another male to help guide him through aspects that being a mom, you want to be there but knowing it’s not the same. How do you get him to understand your fears are warranted and your not just being overprotective?

Marlena: We have talks no matter what the situation is even if we had a bad one at first, we always have a great one afterward. He doesn’t always want to hear things sometimes but he does listen.

We always hear about African American men being in danger, what are your fears for your daughter?

Marlena: They are the same as my son. The same rules apply. In my eyes the dangers are the same no matter rather you are male or female.

Your children are your world how are you able to keep them motivated that everything will be ok even when your not around?

Marlena: I always teach them things every day to help them in the future. I also remind them about how I was from the time they were babies.

What advice would you give to a single mom who is struggling to win the battle from the streets influences?

Marlena: Never put too much fear in them that they have more comfort in the streets instead of their own home.

How would you describe your children?

Marlena: I have two completely personalities for both. One is more laid back and chill while the other one is dramatic and crazy.

Whats your motto for being a mom?

Marlena: They make your life so crazy but interesting.

Serving in the military is something that not everyone can do. It takes extraordinarily people to be able to become a soldier and to be black and in the military is an amazing accomplishment and being a woman makes it beyond extraordinary. Today we will be looking into who was the first and how African American women have made a pathway in the military for future generations to serve a country that they love to protect.

One local officer is working to bring more diversity and inclusion into the U.S. Navy. Captain Timika (Timi) Lindsay is currently the highest ranking African American woman in the Navy. She is the Chief Diversity Officer and the Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at the U.S. Naval Academy.

The Women’s Armed Services Integration Act of 1948. 1949 – First black female Marines enlisted. The first African-American woman, Annie E. Graham of Detroit, Michigan, enlisted in the Marines.

Marcia Carol Martin Anderson (née Mahan; born 1957) is a retired senior officer of the United States Army Reserve. She was the first African-American woman to become a major general in the United States Army Reserve.

Once again, the Air Force, with 13.5 percent, has the largest share of women, and the Marine Corps, with 5.2 percent, has the smallest. The Army, with 11.0 percent women, follows the Air Force; and the Navy and the Coast Guard are made up of 7.3 percent and 6.3 percent women, respectively.

Shawna Rochelle Kimbrell is a Lieutenant Colonel in the United States Air Force, and the first female African-American fighter pilot in the history of that service.

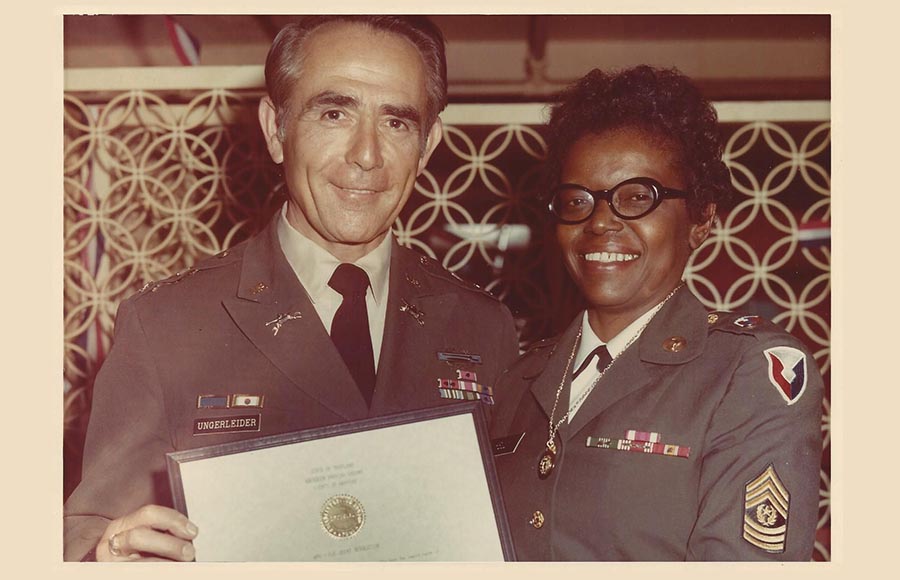

Mildred C. Kelly served in the U.S. Army from March 1947 to April 1976. The Army wasn’t her first career choice. She attended and graduated from Knoxville College in Tennessee with a degree in chemistry. After graduation, she briefly taught high school before deciding to join the Army. In 1972, she became the first Black female Sergeant Major in the U.S. Army. Two years later in 1974, she made ranks of the first Black female command sergeant major at Aberdeen Proving Ground. This made her the first Black woman to hold the highest enlisted position at a major Army installation whose population was predominantly male. After retirement, she continued to serve in a different capacity by remaining active on various boards such as the Women in Military Service for America Memorial Foundation, Maryland Veterans Commission and the Veterans Advisory Board. Command Sgt. Maj. Mildred C. Kelly passed away from cancer in 2003.

Staff Sgt. Joyce B. Malone: Malone was originally a Fayetteville civic leader who enlisted in the Marines in 1958, where she served four years. Following her service in the Marine Corps in 1962, Malone got married and finished college at Fayetteville State University. A few years went by and while working at Fort Bragg, she decided to join the Army Reserve – Fort Bragg’s 82nd Airborne Division in 1971. In 1974, Malone became the first and the oldest black woman to earn Airborne wings in the United States Army Reserve. By age 38, Malone completed 15 parachute jumps during her time in the Army Reserve.

Brig. Gen. Hazel W. Johnson-Brown: Becoming a nurse was Hazel W. Johnson-Brown’s dream. She attended the Harlem School of Nursing. Her career began at the Harlem Hospital as an operating room nurse after completing her studies. In 1955, seven years after President Truman eliminated segregation in the military, Hazel W. Johnson-Brown made the decision to enlist in the U.S. Army. She impressed her superiors with her incredible talent and taking multiple assignments across the world.

One of Johnson-Brown’s assignments included Japan where she trained nurses on their way to Vietnam. She made history after being promoted in 1979 to brigadier general. With that promotion, she took charge of 7,000 nurses in the Army Nurse Corps, making her the first Black woman general officer to hold that post. When Brig. Gen. Johnson-Brown received her promotion, she said, “Race is an incidence of birth …. I hope the criterion for selection did not include race but competence.” Brig. Gen. Johnson-Brown served in the U.S. Army from 1955 to 1983, receiving multiple awards and decorations

Maj. Gen. Marcelite J. Harris was born in Houston, Texas on Jan. 16, 1943. She graduated from Spelman College, earning her Bachelor of Arts degree in speech and drama. She originally wanted to be an actress, but her plans changed so she signed up for the Air Force. In 1965 she completed Officer Training School at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas and held a variety of assignments in the Air Force.

Harris’ career included many “firsts,” including being the first female aircraft maintenance officer, one of the first two female air officers commanding at the United States Air Force Academy and the Air Force’s first female director of maintenance. She also served as a White House social aide during the Carter administration. Her service medals and decorations include the Bronze Star, the Presidential Unit Citation and the Vietnam Service Medal.

Harris retired as a major general in 1997, the highest ranking female officer in the Air Force, and the nation’s highest ranking African-American woman in the Department of Defense. She died in 2018.

Sgt. Danyell Wilson: Wilson served in the U.S. Army and became the first African-American woman to earn the prestigious Tomb Guard Badge. She became a sentinel at the Tomb of the Unknowns, Jan. 22, 1997.

Born in 1974 in Montgomery, Alabama, Wilson joined the Army in February 1993. She was a military police officer assigned to the MP Company, 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard). She completed testing and a rigorous training period and became part of the Honor Guard Company of The Old Guard.

After receiving the silver emblem, Wilson said she was glad the training was over. “I figured it (finishing the training) was the highest honor,” she said before making her first official “high-visibility” walk.

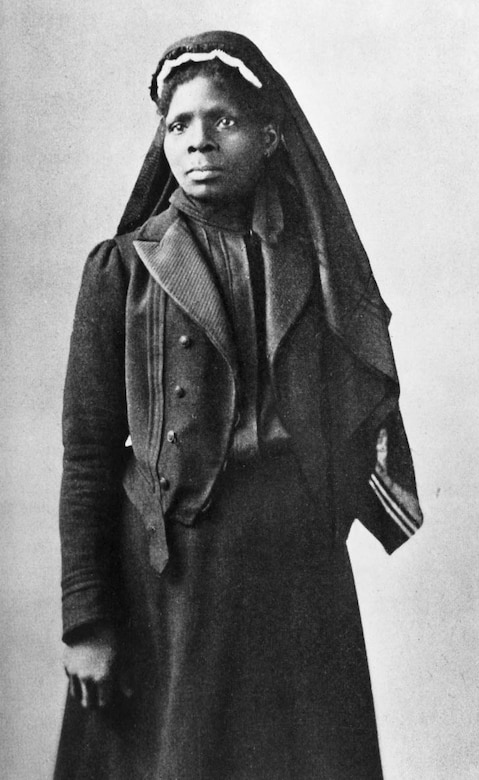

Susie King Taylor was appointed laundress of the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War and due to her nursing skills and her ability to read and write, her responsibilities with the regiment grew tremendously. Photo courtesy of U.S. Center for Military History

WRIGHT-PATTERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Ohio (AFNS) —

February is the celebration of African American history and the accomplishments of Black people around the world. There are many female pioneers in African American history with various accomplishments that come to mind. Some of these pioneers are Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Rosa Parks, Madam C.J. Walker and Shirley Chisholm. Many black women also broke barriers while serving in the U.S. Military. These women worked on the front lines or provided support to U.S. soldiers and civilian employees.

There are many more that we have in history that we should be proud of. These are just a few that I wanted to share with everyone hoping that people can see another side of African American history.

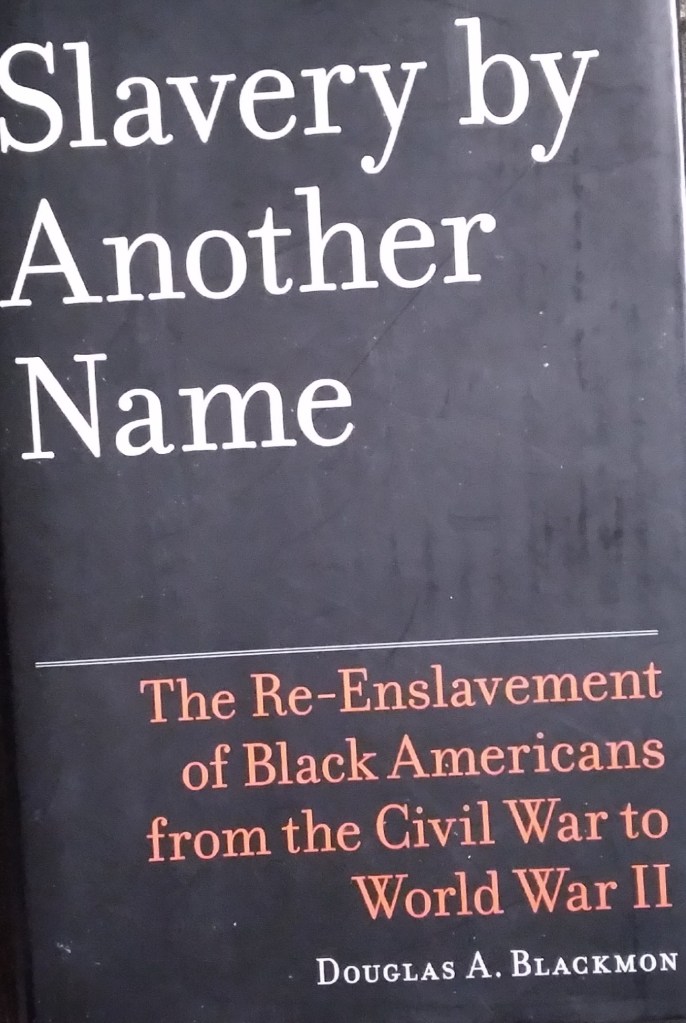

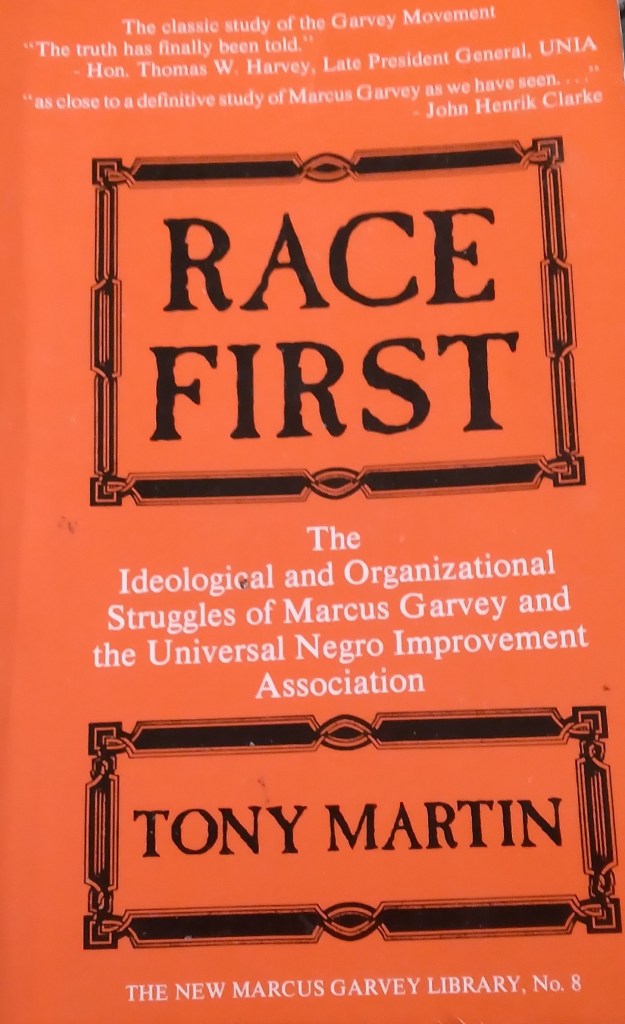

Its sad to say that in today’s world how Black history is being shown to today’s youth with so much information not being taught where it comes across as a way to leave disturbing actions by others hidden. True there’s no secret that African Americans’history didn’t start in a positive light. There were so many tragic actions from different forms of killings to rapes and any rights being taken away because of the color of their skin. In today’s time we still see people being smuggled to different countries and we were ones as well back in those horrific times. True we have movies and books to help fill in the gaps that schools choose not to teach but as with any History I believe ALL history needs to be known not just the ones you can stomach but also the parts we can’t.

It’s tragic to know that I know adults and children who don’t know about Emmet Till and how this child’s death helped the fight for civil rights in america. So I see everyday the importance of keeping African American history narrative alive and most important accurate for future generations to understand the fighting spirit that continues to this day and why. To understand why it’s difficult for what we should have and that’s the rights ancestors died for but yet isn’t given to us still unless you fight for it even in today’s world. I hope someone gets a better understanding or a refresher from this post and the motivation for themselves to look deeper than what a classroom tells about a culture that is rich in history and why it is in many forms still feared.

enjoy.

“The first example we have of Africans being taken against their will and put on board European ships would take the story back to 1441,” says Guasco, when the Portuguese captured 12 Africans in Cabo Branco—modern-day Mauritania in north Africa—and brought them to Portugal as enslaved peoples. Passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, the 13th amendment abolished slavery in the United States and provides that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States,

in 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “all persons held as slaves… shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free,” effective January 1, 1863. It was not until the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, in 1865, that slavery was formally abolished ( here ).

Sometime in 1619, a Portuguese slave ship, the São João Bautista, traveled across the Atlantic Ocean with a hull filled with human cargo: captive Africans from Angola, in southwestern Africa. The men, women and children, most likely from the kingdoms of Ndongo and Kongo, endured the horrific journey, bound for a life of enslavement in Mexico. Almost half the captives had died by the time the ship was seized by two English pirate ships; the remaining Africans were taken to Point Comfort, a port near Jamestown, the capital of the English colony of Virginia, which the Virginia Company of London had established 12 years earlier. The colonist John Rolfe wrote to Sir Edwin Sandys, of the Virginia Company, that in August 1619, a “Dutch man of war” arrived in the colony and “brought not anything but 20 and odd Negroes, which the governor and cape merchant bought for victuals.” The Africans were most likely put to work in the tobacco fields that had recently been established in the area.

Forced labor was not uncommon — Africans and Europeans had been trading goods and people across the Mediterranean for centuries — but enslavement had not been based on race. The trans-Atlantic slave trade, which began as early as the 15th century, introduced a system of slavery that was commercialized, racialized and inherited. Enslaved people were seen not as people at all but as commodities to be bought, sold and exploited. Though people of African descent — free and enslaved — were present in North America as early as the 1500s, the sale of the “20 and odd” African people set the course for what would become slavery in the United States.