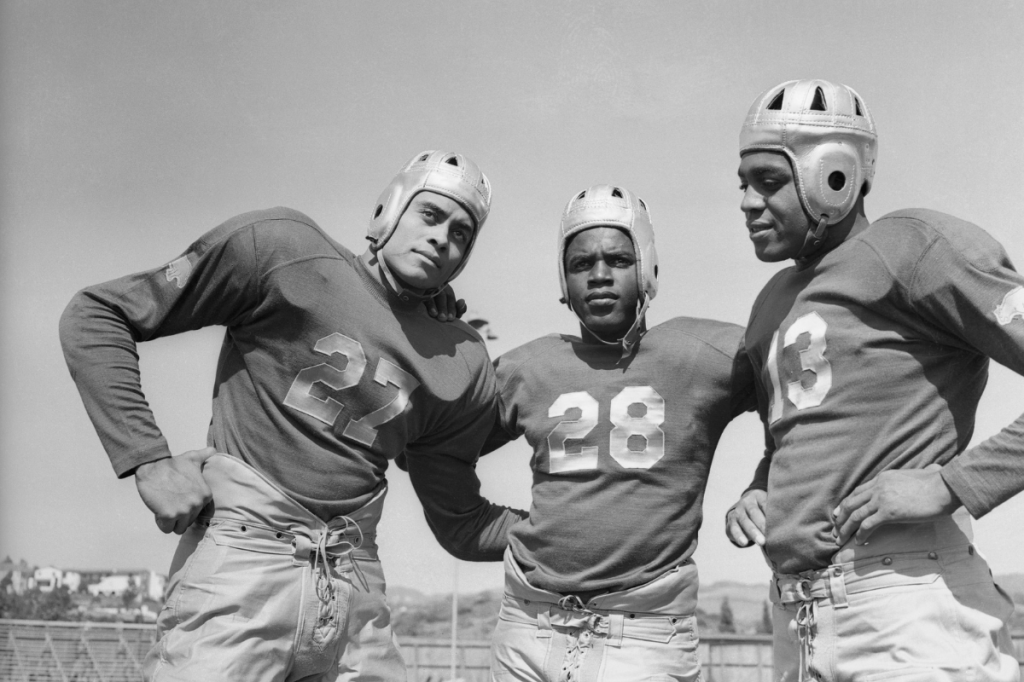

A graduate of New York City’s Music & Art High School, Billy Graham was influenced artistically by the work of Al Williamson, Frank Frazetta, Burne Hogarth, and George Tuska.

One of his earliest comics projects was illustrating writer Don Glut‘s “Death Boat!” in Vampirella #1 (Sept. 1969), one of Warren Publishing‘s influential black-and-white horror-comics magazines. Graham would pencil and self-ink a story in nearly each of the first dozen issues of Vampirella, and an additional tale in issue #32 (April 1970) of its brethren publication Creepy

Publisher James Warren recalled in 1999 that he promoted Graham to art director shortly after recruiting him as an artist:

I sensed Billy had the ability to handle it; certain artists and writers are great but they can’t shift out of their specialty and do something else. Billy could. So I said, ‘Billy, you are now art director! Whether you like it or not.’ Now you have to understand that all Billy wanted to do his whole life was just be Jack Kirby. I said, ‘ You’ll be the Black Jack Kirby, but not today! Today you are art director of Warren Publishing.’ But he said, ‘I can’t art direct!’ And I said, ‘I’ll show you how. There’s your office; you now have a full-time job. A paycheck every Friday. Do you accept?’ And he said, ‘Yer goddamn right!’ And I taught him how to art direct during our slow period, and it only took a couple of issues — and he did pretty well (though I gave him a nervous breakdown).

In a 2005 interview, Warren mentions tweaking a Rolling Stone reporter who asked about his decision to hire an African-American art director, a rarity in comics at the time: “‘What!?’ mock-screamed Warren. ‘Is Billy black? I didn’t know that. Get him in here! Billy, are you black? You’re fired!

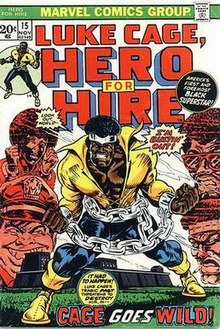

Graham eventually left Warren and joined the creative team that launched Marvel’s Luke Cage, Hero for Hire, inking the premiere issue (June 1972) over pencilers John Romita Sr. and George Tuska. He either inked or himself penciled every issue of the book’s 16–issue run under its original title, and the first as the retitled Luke Cage, Power Man (Feb. 1974). One reviewer of the reprint collection Essential Luke Cage, Power Man wrote, “The majority of the art is by George Tuska, initially inked by Billy Graham (with several solo pieces by Graham [that] give an intriguing record of his progression as an artist: His initial work has a rough, half-finished look to it, but his later issues are clean and beautifully detailed)….

Steve Englehart, who wrote issues #5–16, said Graham “helped me plot, so that by the end it was pretty much a co-production.” Graham is formally credited as co-writer of issues #14-15, though as Englehart’s writing collaborator for those issues, Tony Isabella, recalled, “Billy Graham is credited as the co-scripter of my first issue [#15] and, try as I might, I simply do not recall getting anything other than the usual penciled pages to script. I skimmed a little of that issue and, making no judgment as to whether this is a good or bad thing, the writing does strike me as all mine.”

Graham collaborated with writer Don McGregor on the critically lauded “Black Panther” series that ran in Jungle Action #6–24 (Sept. 1973–Nov. 1976), becoming the series’ regular penciler with issue #11 (Sept. 1974) and leaving after penciling the first five pages of issue #22 (July 1976).[4] Bob Almond, inker for much of the run of The Black Panther vol. 3, dedicated his work in memoriam to Graham in an introductory note to issue #17 (April 2000). The pseudonymous Buzz Maverik wrote in Ain’t It Cool News, “I know the [Jungle Action] artist, Billy Graham, was black. His cool Marvel Bullpen name was ‘The Irreverent’ Billy Graham. For me, even though I later learned that Jack Kirby created the Panther, Graham will always be the definitive Panther artist. His art, even more than McGregor’s writing, made T’Challa one of what I call the ‘grown men’ of the Marvel Universe, the others being Daredevil and Iron Man. Those three seemed like the kind of

adult I aspired to be, with cool jobs, cool hobbies (superheroing), and cool chicks.” In 2010, Comics Bulletin ranked McGregor and Graham’s run on Jungle Action third on its list of the “Top 10 1970s Marvels”.

Graham illustrated issues #3–9 of McGregor’s 1980s Eclipse Comics series Sabre, a spin-off of one of the first graphic novels. He also illustrated a story each by McGregor in Marvel’s black-and-white horror-comics magazine Monsters Unleashed #11 (April 1975); an issue of the 1980s anthology Eclipse Monthly; and two issues of the black-and-white Eclipse Magazine. He was both writer and artist of the six-page story “The Hitchhiker” in Eclipse Magazine #5 (March 1982).

He additionally illustrated the Marvel story “More Than Blood”, scripted by science-fiction author George Alec Effinger, in Journey into Mystery vol. 2, #2 (Dec. 1972); and two “Gabriel: Devil-Hunter” stories by Doug Moench in the black-and-white magazine Haunt of Horror #2–3 (July–Aug. 1974), as well as a Moench story in the black-and-white Vampire Tales #7 (Oct. 1974).

Graham’s last comics work was co-penciling, with Steven Geiger, Power Man and Iron Fist (the again-retitled Luke Cage series) #114 (Feb. 1985), written by Jim Owsley, who would later write the Black Panther under his pen name, Christopher Priest

Graham appeared as an extra in TV commercials for products including beer and chewing gum, and played the artist father of one of the lead characters in McGregor’s unreleased, low-budget film adaptation of his Detectives Inc. graphic novels. Graham wrote several plays and received awards for his set design work as well.

Bibliography

Eclipse Comics

- Eclipse Magazine #2, 4–5 (1981–1982)

- Eclipse Monthly #8 (1984)

- Sabre #3–9 (1982–1984)

Marvel Comics

- Haunt of Horror #2–3 (1974)

- Hero for Hire #1–16 (1972–1973)

- Journey into Mystery vol. 2 #2 (1972)

- Jungle Action #10–22 (Black Panther) (1974–1976)

- Monsters Unleashed #11 (1975)

- Power Man #17 (1974)

- Power Man and Iron Fist #114 (1985)

- Vampire Tales #7 (1974)

Warren Publishing

- Creepy #32 (1970)

- Eerie #28, 31 (1970–1971)

- Vampirella #1–3, 5, 7–8, 10, 12 (1969–1971)

If you have any questions please don’t hesitate to call DAWN at 832-393-4055

If you have any questions please don’t hesitate to call DAWN at 832-393-4055