Madam C.J. Walker (born Sarah Breedlove; December 23, 1867 – May 25, 1919) was an African American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and political and social activist. She is recorded as the first female self-made millionaire in America in the Guinness Book of World Records. Multiple sources mention that although other women (like Mary Ellen Pleasant) might have been the first, their wealth is not as well-documented.

Walker made her fortune by developing and marketing a line of cosmetics and hair care products for black women through the business she founded, Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. She became known also for her philanthropy and activism. She made financial donations to numerous organizations and became a patron of the arts. Villa Lewaro, Walker’s lavish estate in Irvington, New York, served as a social gathering place for the African-American community. At the time of her death, she was considered the wealthiest African-American businesswoman and wealthiest self-made black woman in America. Her name was a version of “Mrs. Charles Joseph Walker,” after her third husband.

Early life

Sarah Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, close to Delta, Louisiana. Her parents were Owen and Minerva (Anderson) Breedlove.She had five siblings, who included an older sister, Louvenia, and four brothers: Alexander, James, Solomon, and Owen Jr. Her older siblings were enslaved by Robert W. Burney on his Madison Parish plantation. Sarah was the first child in her family born into freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. Her mother died in 1872, likely from cholera (an epidemic traveled with river passengers up the Mississippi, reaching Tennessee and related areas in 1873). Her father remarried but died a year later.

She was orphaned at the age of seven. Sarah moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, at the age of 10, where she lived with Louvenia and her brother-in-law, Jesse Powell. She started working as a child as a domestic servant. “I had little or no opportunity when I started out in life, having been left an orphan and being without mother or father since I was seven years of age,” she often recounted. She also recounted that she had only three months of formal education, which she learned during Sunday school literacy lessons at the church she attended during her earlier years.

Marriage and family

In 1882, at the age of 14, Sarah married 22-year old Moses McWilliams to escape abuse from her brother-in-law, Jesse Powell. Sarah and Moses had one daughter, Lelia McWilliams, who was born on June 6, 1885. When Moses died in 1887, Sarah was twenty and Lelia was two. Sarah remarried in 1894, but left her second husband, John Davis, around 1903.

In January 1906, Sarah married Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman she had known in St. Louis, Missouri. Through this marriage, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker. The couple divorced in 1912; Charles died in 1926. Lelia McWilliams adopted her stepfather’s surname and became known as A’Lelia Walker.

Career

C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1911

In 1888, she and her daughter moved to St. Louis, where three of her brothers lived. Sarah found work as a laundress, earning barely more than a dollar a day. She was determined to make enough money to provide her daughter with formal education. During the 1880s, she lived in a community where Ragtime music was developed; she sang at St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and started to yearn for an educated life as she watched the community of women at her church.

Sarah suffered severe dandruff and other scalp ailments, including baldness, due to skin disorders and the application of harsh products to cleanse hair and wash clothes. Other contributing factors to her hair loss included poor diet, illnesses, and infrequent bathing and hair washing during a time when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing, central heating, and electricity.

Madam C. J. Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower in the permanent collection of The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis

Initially, Sarah learned about hair care from her brothers, who were barbers in St. Louis. Around the time of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World’s Fair at St. Louis in 1904), she became a commission agent selling products for Annie Malone, an African-American hair-care entrepreneur, millionaire, and owner of the Poro Company. Sales at the exposition were a disappointment since the African-American community was largely ignored.

While working for Malone, who would later become Walker’s largest rival in the hair-care industry, Sarah began to take her new knowledge and develop her own product line. In July 1905, when she was 37 years old, Sarah and her daughter moved to Denver, Colorado, where she continued to sell products for Malone and develop her own hair-care business. A controversy developed between Annie Malone and Sarah because Malone accused Sarah of stealing her formula, a mixture of petroleum jelly and sulfur that had been in use for a hundred years.

Following her marriage to Charles Walker in 1906, Sarah became known as Madam C. J. Walker. She marketed herself as an independent hairdresser and retailer of cosmetic creams. (“Madam” was adopted from women pioneers of the French beauty industry.) Her husband, who was also her business partner, provided advice on advertising and promotion; Sarah sold her products door to door, teaching other black women how to groom and style their hair.

In 1906, Walker put her daughter in charge of the mail-order operation in Denver while she and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern United States to expand the business. In 1908, Walker and her husband relocated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where they opened a beauty parlor and established Lelia College to train “hair culturists.” As an advocate of black women’s economic independence, she opened training programs in the “Walker System” for her national network of licensed sales agents who earned healthy commissions (Michaels, PhD. 2015).

After Walker closed the business in Denver in 1907, A’lelia ran the day-to-day operations from Pittsburgh. In 1910, Walker established a new base in Indianapolis. A’lelia also persuaded her mother to establish an office and beauty salon in New York City‘s growing Harlem neighborhood in 1913; it became a center of African-American culture.

In 1910, Walker relocated her businesses to Indianapolis, where she established the headquarters for the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. She initially purchased a house and factory at 640 North West Street. Walker later built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents, and added a laboratory to help with research. She also assembled a staff that included Freeman Ransom, Robert Lee Brokenburr, Alice Kelly, and Marjorie Joyner, among others, to assist in managing the growing company. Many of her company’s employees, including those in key management and staff positions, were women.

Walker’s method of grooming was designed to promote hair growth and to condition the scalp through the use of her products. The system included a shampoo, a pomade stated to help hair grow, strenuous brushing, and applying iron combs to hair; the method claimed to make lackluster and brittle hair become soft and luxuriant. Walker’s product line had several competitors. Similar products were produced in Europe and manufactured by other companies in the United States, which included her major rivals, Annie Turnbo Malone’s Poro System from which she derived her original formula and later, Sarah Spencer Washington’s Apex System.

Between 1911 and 1919, during the height of her career, Walker and her company employed several thousand women as sales agents for its products. By 1917, the company claimed to have trained nearly 20,000 women. Dressed in a characteristic uniform of white shirts and black skirts and carrying black satchels, they visited houses around the United States and in the Caribbean offering Walker’s hair pomade and other products packaged in tin containers carrying her image. Walker understood the power of advertising and brand awareness. Heavy advertising, primarily in African-American newspapers and magazines, in addition to Walker’s frequent travels to promote her products, helped make Walker and her products well known in the United States.

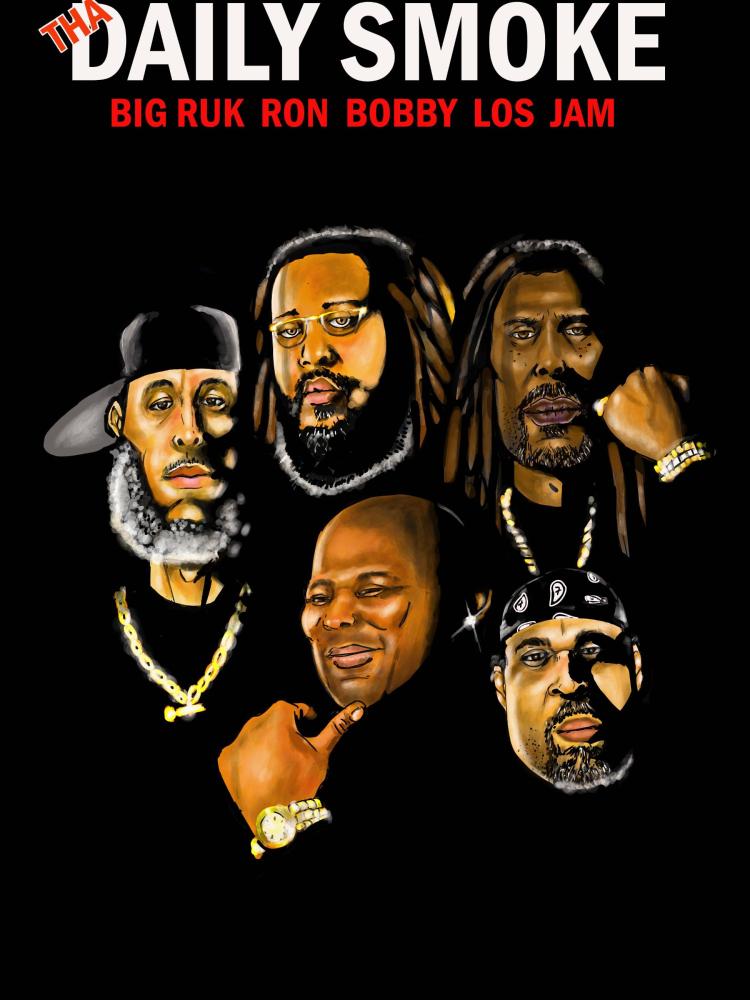

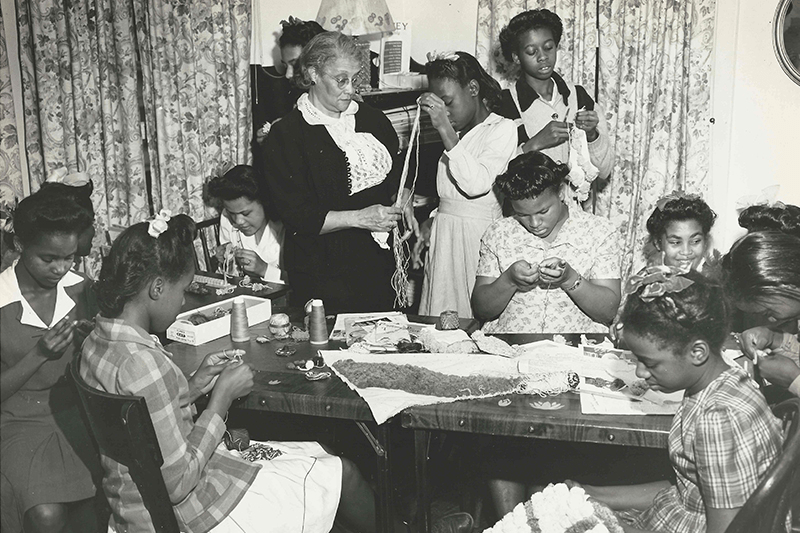

In addition to training in sales and grooming, Walker showed other black women how to budget, build their own businesses, and encouraged them to become financially independent. In 1917, inspired by the model of the National Association of Colored Women, Walker began organizing her sales agents into state and local clubs. The result was the establishment of the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents (predecessor to the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union of America).

Its first annual conference convened in Philadelphia during the summer of 1917 with 200 attendees. The conference is believed to have been among the first national gatherings of women entrepreneurs to discuss business and commerce. During the convention Walker gave prizes to women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents. She also rewarded those who made the largest contributions to charities in their communities.

Walker’s name became even more widely known by the 1920s, after her death, as her company’s business market expanded beyond the United States to Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Panama, and Costa Rica.

Activism and philanthropy

Walker’s home at 67 Broadway in Irvington, New York

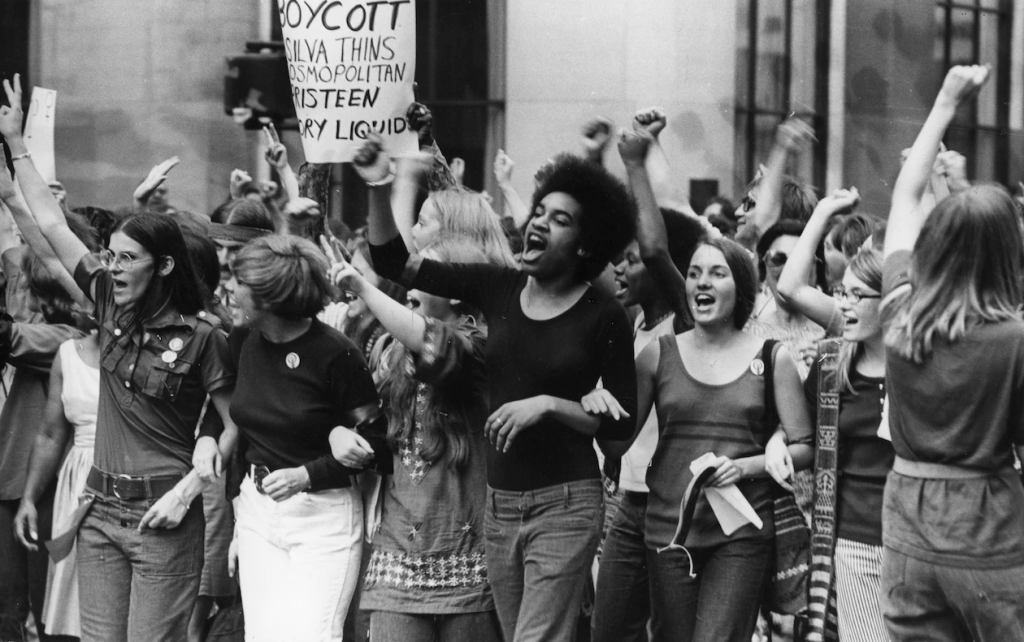

As Walker’s wealth and notoriety increased, she became more vocal about her views. In 1912, Walker addressed an annual gathering of the National Negro Business League (NNBL) from the convention floor, where she declared: “I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there, I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.” The following year she addressed convention-goers from the podium as a keynote speaker.

She helped raise funds to establish a branch of YMCA in Indianapolis’s black community, pledging $1,000 to the building fund for Senate Avenue YMCA. Walker also contributed scholarship funds to the Tuskegee Institute. Other beneficiaries included Indianapolis’s Flanner House and Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church; Mary McLeod Bethune’s Daytona Education and Industrial School for Negro Girls (which later became Bethune-Cookman University) in Daytona Beach, Florida; the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina; and the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in Georgia. Walker was also a patron of the arts.

About 1913, Walker’s daughter, A’Lelia, moved to a new townhouse in Harlem, and in 1916, Walker joined her in New York, leaving the day-to-day operation of her company to her management team in Indianapolis. In 1917, Walker commissioned Vertner Tandy, the first licensed black architect in New York City and a founding member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, to design her house in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York. Walker intended for Villa Lewaro, which cost $250,000 to build, to become a gathering place for community leaders and to inspire other African Americans to pursue their dreams. She moved into the house in May 1918 and hosted an opening event to honor Emmett Jay Scott, at that time the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the U.S. Department of War.

Walker became more involved in political matters after her move to New York. She delivered lectures on political, economic, and social issues at conventions sponsored by powerful black institutions. Her friends and associates included Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, and W. E. B. Du Bois. During World War I, Walker was a leader in the Circle For Negro War Relief and advocated for the establishment of a training camp for black army officers. In 1917, she joined the executive committee of New York chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which organized the Silent Protest Parade on New York City’s Fifth Avenue. The public demonstration drew more than 8,000 African Americans to protest a riot in East Saint Louis that killed 39 African-Americans. Also, from 1917 until her death she was a member of the Committee of Management of the Harlem YWCA, influencing development of training in beauty skills to young women by the organisation.

Profits from her business significantly impacted Walker’s contributions to her political and philanthropic interests. In 1918, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC) honored Walker for making the largest individual contribution to help preserve Frederick Douglass‘s Anacostia house. Before her death in 1919, Walker pledged $5,000 (the equivalent of about $77,700 in 2019) to the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund. At the time, it was the largest gift from an individual that the NAACP had ever received. Walker bequeathed nearly $100,000 to orphanages, institutions, and individuals; her will directed two-thirds of future net profits of her estate to charity

Death and legacy

The grave of Madam C. J. Walker

Walker died on May 25, 1919, from kidney failure and complications of hypertension at the age of 51. Walker’s remains are interred in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York City.

At the time of her death, Walker was considered to be worth between a half million and a million dollars. She was the wealthiest African-American woman in America. According to Walker’s obituary in The New York Times, “she said herself two years ago [in 1917] that she was not yet a millionaire, but hoped to be some time, not that she wanted the money for herself, but for the good she could do with it.” The obituary also noted that same year, her $250,000 mansion was completed at the banks of the Hudson at Irvington. Her daughter, A’Lelia Walker, later became the president of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company.

Walker’s personal papers are preserved at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis. Her legacy also continues through two properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Villa Lewaro in Irvington, New York, and the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Villa Lewaro was sold following A’Lelia Walker’s death to a fraternal organization called the Companions of the Forest in America in 1932. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has designated the privately owned property a National Treasure.

Indianapolis’s Walker Manufacturing Company headquarters building, renamed the Madame Walker Theater Center, opened in December 1927. It included the company’s offices and factory as well as a theater, beauty school, hair salon and barbershop, restaurant, drugstore, and a ballroom for the community. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

A museum in Atlanta is devoted to Walker, as well as historic radio station WERD. Established in 2004, the museum is located at the site of a former Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Shoppe.

In 2006, playwright and director Regina Taylor wrote The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove, recounting the history of Walker’s struggles and success. The play premiered at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago. Actress L. Scott Caldwell played the role of Walker.

On March 4, 2016, Sundial Brands, a skincare and haircare company, launched a collaboration with Sephora in honor of Walker’s legacy. The line, titled “Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture,” comprised four collections and focused on the use of natural ingredients to care for different types of hair.

TV series

In 2020, actress Octavia Spencer committed to portray Walker in a TV series based on the biography of Walker written by Walker’s great-great-granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles. The series is called Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker. Reviews for the series were mixed because of the inaccuracies of the story line that created more of a fictional work than an authentic biography. The portrayal of Annie Malone as Addie Monroe, another black female self-made millionaire as a villain and the daughter of Walker as a lesbian were some of the complaints by audiences.

Documentary

Madam Walker is featured in Stanley Nelson‘s 1987 documentary, Two Dollars and a Dream, the first film treatment of Walker’s life. As the grandson of Freeman B. Ransom, Madam Walker’s attorney and Walker Company general manager, Nelson had access to original Walker business records and former Walker Company employees whom he interviewed during the 1980s.

Tributes

Various scholarships and awards have been named in Walker’s honor:

- The Madam C. J. Walker Business and Community Recognition Awards are sponsored by the National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Oakland / Bay Area chapter. An annual luncheon honors Walker and awards outstanding women in the community with scholarships.

- Spirit Awards have sponsored the Madame Walker Theater Center in Indianapolis. Established as a tribute to Walker, the annual award has honored national leaders in entrepreneurship, philanthropy, civic engagement, and the arts since 2006. Awards presented to individuals include the Madame C. J. Walker Heritage Award as well as young entrepreneur and legacy prizes.

Walker was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1993. In 1998, the U.S. Postal Service issued a Madam Walker commemorative stamp as part of its Black Heritage Series.