Poetry, Arts, Cooking, Communication, Culture and More!

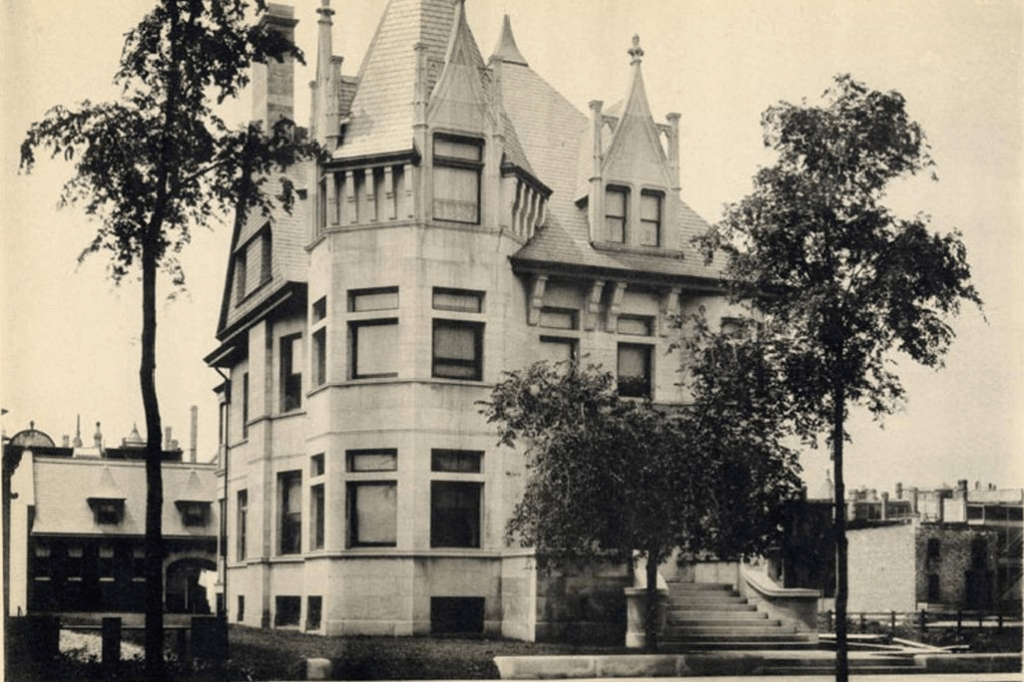

Today, the DuSable Museum of African American History is a Chicago landmark. In 1961, it was started in the living room of Margaret Taylor-Burroughs.Born on this day in 1915, Taylor-Burroughs started what was then called the Ebony Museum of Negro History in the downstairs of her house with a group of other concerned citizens and her husband, Charles Burroughs. The museum, which is the oldest independently owned museum of black culture in the United States, was created to preserve, study and teach black history and art.

She was extremely qualified for the job as a longtime teacher, artist and public historian. Taylor-Burroughs, who died in 2010, described how she founded the museum and its early years in an interview with public historian John E. Fleming in 1999.

“We collected various things and when people heard what we were doing they had various things, and they brought them, and we cleared all of the furniture out of the first-floor parlor for the museum,” she said.

In the beginning, the small museum taught classes on how to teach black history, she said. Students started visiting. By 1973, the museum needed more space and moved into its current digs within Washington Park. Today, it’s a Smithsonian affiliate, and its collections include a significant collection of 19th and 20th century works by African-American artists, such as the Freedom Mural and historical artifacts like this quilt cover made in 1900, as well as an archives.

Its name also changed. Taylor-Burroughs said that the word “Ebony” was removed from the name partly because it was the name of Ebony Magazine, which was headquartered nearby. In time, it took on the name DuSable after Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, who was Chicago’s first non-indigenous settler according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago. DuSable was an Afro-French fur trader, the encyclopedia writes.

“The DuSable quickly became a resource for teaching African American history and culture and a focal point in Chicago for black social activism,” writes the encyclopedia, “particularly because of limited cultural resources then available to Chicago’s large black population. Through the years, the museum has served as nerve center for political fundraisers, community festivals, and social and civic events serving the black community.”

The Ebony Museum was one of a number of “neighbourhood museums” dealing with black history that were founded in the United States in the 1960s, writes historian Andrea A. Burns.

“While battling often adverse conditions, the leaders of these institutions elevated the recognition of black history and culture, provided space for community gatherings, and attempted to develop a strong sense of identity and self-affirmation among African-American audiences,” she writes.

“We weren’t started by anybody downtown; we were started by ordinary folks,” Taylor-Burroughs said about the DuSable.

A new exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts explores the trailblazing Black artists who overcame discrimination and prejudice to make their mark on film history. “Regeneration: Black Cinema, 1898–1971,” which previously opened at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in 2022, features nearly 200 costumes, props, posters, photographs, newsreels, home movies and other artifacts spread throughout nine gallery spaces. The institute’s Detroit Film Theater is also hosting a film series to showcase more than 20 Black movies—including The Flying Ace(1926) and Harlem on the Prairie (1937)—in connection with the exhibition.

The idea for the show was born when co-curator Doris Berger, vice president of curatorial affairs at the Academy Museum, discovered a rich trove of posters and lobby cards connected to Black cinema in the museum’s archives.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1a/7d/1a7d6adf-a635-49e4-a75e-8fb6a09a28fa/e202361_harlemontheprairieposter.jpg)

“I realized, ‘Oh my God, there’s so much history there that the wider public might not know as much [about],’” she tells the Detroit News’ Erica Hobbs.

When museum-goers first enter the exhibition, they’re greeted by a large projection of Something Good‑Negro Kiss, an 1898 silent film that shows actors Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown flirting, laughing and kissing. Directed by William Selig, the pioneering short film is known as the “first on-screen depiction of Black intimacy,” writes the Detroit Free Press’ Duante Beddingfield.

Historians thought Something Good‑Negro Kiss had been lost to history. But in 2017, the film’s 19th-century nitrate negative resurfaced. After its discovery, the film was inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2018.

A dress worn by Lena Horne in 1943’s Stormy Weather was similarly challenging to track down. Costumes worn by Black actors tend to be “much more difficult to identify and find than their white counterparts,” says co-curator Rhea L. Combs, director of curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, to the Detroit News.

“They would get repurposed, they would be used elsewhere, just lost to time,” she adds. “So being able to identify this and confirm that it was actually worn by Lena Horne and then to be able to present it, is a real coup when it comes to film history.”

The exhibition will also showcase the tap shoes worn by Harold and Fayard Nicholas during the “Jumpin’ Jive” dance number in Stormy Weather. The scene shows the brothers performing complex choreography and was filmed in one take.

“It’s more impressive to know that [Harold and Fayard] were self-taught and never had a formal dance lesson in their lives,” said Nicole Nicholas, Fayard Nicholas’ granddaughter, at a media preview of the exhibition, per the Detroit Free Press.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a2/00/a2002bc7-e84f-4629-90d3-91508427c523/31_louise_beavers_in_reform_school.jpg)

Other artifacts on view include home movies from Josephine Baker and Cab Calloway, which offer an intimate look at Black performers’ private lives. Visitors can learn more about Oscar Micheaux, a Black novelist-turned-filmmaker who created more than 40 movies between 1918 and 1948, and see the Academy Award for Best Actor that Sidney Poitier won for the 1963 film Lilies of the Field.

“This critically important presentation chronicles much of what we know on-screen but shares so much more of what happened off-screen,” says Elliot Wilhelm, the institute’s film curator, in a statement.

“Regeneration: Black Cinema, 1898–1971” is on view at the Detroit Institute of Arts through June 23.

Sarah Kuta – Daily Correspondent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)

Jonathan W. White – Author, A House Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House

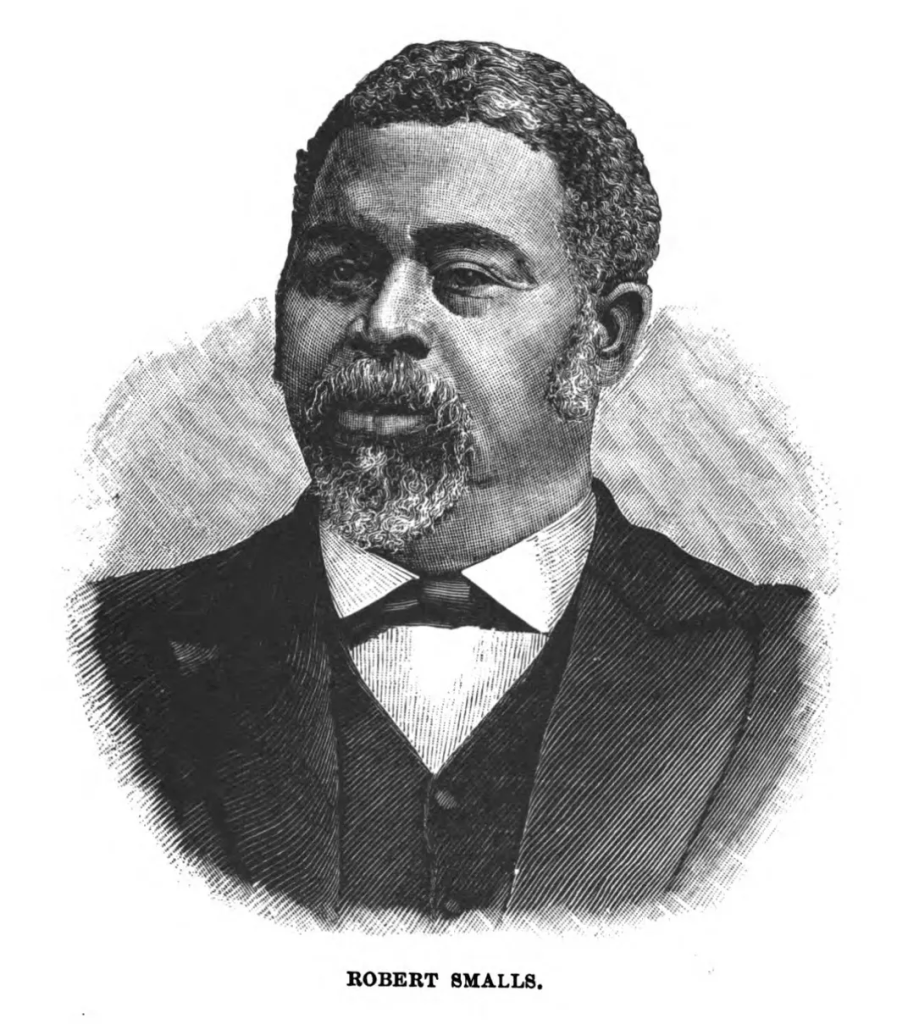

A white Baptist woman named Harriet M. Buss taught Civil War hero Robert Smalls (pictured) how to read and write. Illustration by Meilan Solly / Images via Wikimedia Commons under public domain

When Harriet M. Buss, a white, educated Baptist woman from Massachusetts, moved to South Carolina to accept a position as a teacher in March 1863, she likely didn’t anticipate that one of her students, Robert Smalls, would go on to become a member of the United States House of Representatives. But the Civil War opened up new opportunities for Black Americans like Smalls—a formerly enslaved man who rose to national prominence after sailing a Confederate ship to freedom in 1862—and many seized every chance they could to gain an education and improve their lives. Buss taught hundreds of freedpeople over the course of her career. Her letters home provide not only an extraordinary account of the daily experiences of African Americans as they emerged from bondage but also a unique window into Smalls’ life after his daring escape from slavery.

Little is known about Buss’ childhood (and no photograph of her appears to survive), although she later recalled that she “always thought teaching was my lifework; I longed for it, I aimed and planned for it as soon as I knew what a school was.” Born in 1826 in Sterling, Massachusetts, Buss grew up to be a highly independent, well-traveled woman. Never married, she told her parents, “I don’t want to obey one of creation’s lords. Never could I be told to go or stay, do this or that, and surely never could I ask. I submit to no human being as my master or dictator.”

In the years immediately preceding the Civil War, Buss—then working as an educator in the frontier state of Illinois—wrote with increasing earnestness about national politics. She was incensed by the foolishness and incompetence of the men running the nation and believed that women were better suited to solve America’s problems. “How they so act at Congress, what contemptible and unprincipled men we have there!” she wrote in January 1860.

When Buss learned that Stephen A. Douglas, a Democratic senator from Illinois, was proposing a “sedition” law to silence abolitionist speech, she opined, “Even if he could stop the men’s tongues, he would find another job after that. He must silence the women’s, too, and that is more than he can do.” If Republican leaders like William H. Seward were thrown in jail, she added, “it will be time for the women to act boldly and decisively; and I for one shall be ready, if I have life and health when that day comes.” Buss found her life’s purpose when she began teaching formerly enslaved people in the South. Between 1863 and 1871, she worked as a teacher in three different regions: the Sea Islands of South Carolina; Norfolk, Virginia; and Raleigh, North Carolina. In this final post, she helped establish Shaw University, a historically Black college.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/a3/33a3e5da-db31-47b6-8ce6-cc12b3722215/n_53_119_shaw_hall_24772202636.jpeg)

When Buss arrived in South Carolina in 1863, she wrote about her students in ways that suggest how culturally removed she felt from them. She wanted to “elevate” the formerly enslaved, and she considered herself a “pioneer.” With condescension, she told her parents that they “would be amused if you could come into my school. You would see darkey traits manifested to your satisfaction.”

Over time, however, Buss came to see herself as sharing a mission with her students. She believed the most important thing she could do was to help empower the next generation of Black teachers and ministers through education. “The longer I am engaged in this work,” she wrote in 1869, “the more do I find to convince me that the great masses of this people are to be reached and elevated by the efforts of well-trained theologians and teachers of their own race.”

Of the many revelations contained in Buss’ correspondence, some of the most noteworthy are what she had to say about Smalls, who would go on to serve in Congress for five terms between 1875 and 1887. On May 13, 1862, Smalls had escaped from bondage by seizing command of a Confederate steamer, the CSS Planter, in Charleston, South Carolina, and sailing to the Union blockading fleet. This bold, dangerous action won freedom for Smalls; his wife and two young children; and 12 other men, women and children.

Illustration of the CSS Planter, the Confederate steamer that Smalls sailed to freedom Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Smalls instantly became a hero in the North. The African Methodist Episcopal minister Henry McNeal Turner called him “a living specimen of unquestionable African heroism.” The New York Tribune similarly proclaimed, with a mix of condescension and amazement, “This man, though Black, is a hero—one of the few history will delight to honor. He has done something for his race and for the world of mankind. … He has added new proof to the evidence that negroes have skill—and courage and tact, and that they will risk their lives for the sake of their liberty.”

In August 1862, Smalls traveled to Washington, D.C., where he met with President Abraham Lincoln. Though no contemporaneous account of that meeting appears to exist, evidence suggests that Smalls helped persuade Lincoln to arm Black men in the Union Army. Up to this point, Lincoln had opposed allowing African Americans to fight in the war, in part because he maintained publicly that the purpose of the war was to preserve the Union, not to end slavery, but also because he feared that Black men might prove cowardly on the battlefield.

Smalls helped convince the commander in chief to make an important change in military and public policy. He returned to South Carolina bearing a letter from the War Department that authorized Black military recruitment. Lincoln would make the policy national a few months later, with the Emancipation Proclamation.

An illustration of Smalls Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Smalls’ escape and rise to national prominence are well known. But undocumented until recently is how he pursued an education. In the spring of 1863, a few months after Smalls returned to Beaufort, South Carolina, from Washington, he began participating in private reading lessons taught by Buss.

On June 11, Buss told her parents that “I have Robert Small[s] (the one who ran that steamer Planter out of Charleston last year) for a private scholar now; he comes to the house every afternoon. He will soon learn to read and write.” Buss also taught Smalls’ daughter Elizabeth “Lizzy” Lydia Smalls, who was just 4 years old when she escaped from slavery with her father in 1862. Lizzy was “as pretty a child as any white child I ever had in school” in the North before the war, Buss wrote. She added that Lizzy “is well-dressed, and always looks neat and clean; I should really like to bring her home with me. … I don’t believe there is a person in Sterling who would not say she was a pretty-looking and pretty-behaved little girl.”

Buss’ letters home preserve fascinating conversations she had with freedpeople in the Carolinas and Virginia during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Perhaps the most historically significant was a discussion she had with Smalls regarding the Confederate war effort. On June 23, 1863, Smalls told Buss that six African Americans “had escaped from Savannah and arrived at Hilton Head last evening.” These Black refugees reported that the Georgia city’s Confederate women were “sadly mourning for the loss of their ram,” the CSS Atlanta, described by Buss as “an ugly-looking craft” captured by the Union earlier that month.

Buss’ June 1863 letters about Smalls and his daughter Jonathan W. White

Smalls then shared his views on Confederate women:

Robert thinks these Southern women are worse than the men. He says if he had his way, he wouldn’t leave one of them alive to tell the tale; he says too that one of the greatest reasons of their being so opposed to having the colored people free [is] they are afraid the colored men will marry their daughters, but he thinks if the colored men were all like him, there wouldn’t be much danger. The Southern women would never get married if they waited for such as he.

None of Smalls’ biographers have utilized Buss’ writings, but they offer important insight into the freedman’s thinking during this formative time in his life. (He was then only 24 years old.) This conversation between teacher and student also speaks to broader political debates that were taking place during the Civil War era. For years, Democrats like Douglas had used racial “amalgamation” as a political wedge to win votes. Douglas routinely accused Republicans of wanting to end slavery so they could “authorize negroes to marry white women.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2f/63/2f6300bc-5d21-420e-ac9f-e09f87f08c5f/heroes_of_the_colored_race_lccn00651114.jpeg)

Smalls’ comments to Buss reveal his political awareness and his vehement rejection of the ways pro-slavery apologists talked about race. Of even greater significance, Smalls found that the white women of the South were far “worse” in their support of the Confederacy than white men. If he could have his way, he said with confidence, he would have them all dead, even though they were noncombatants.

It’s telling that Smalls and Buss developed a relationship that enabled them to speak so candidly with each other. Both were fiercely independent, quick-witted and highly motivated individuals. They saw in each other a willing and trustworthy collaborator who would do what they could to overthrow the system of slavery that existed in the American South. Moreover, their personal interactions had a lasting effect on Smalls’ life. The education that he received in 1863 helped prepare him for his work on the state and national stages, where he served with distinction as a vocal advocate for equality and Black Americans’ political rights.