Poetry

Poetry, Arts, Cooking, Communication, Culture and More!

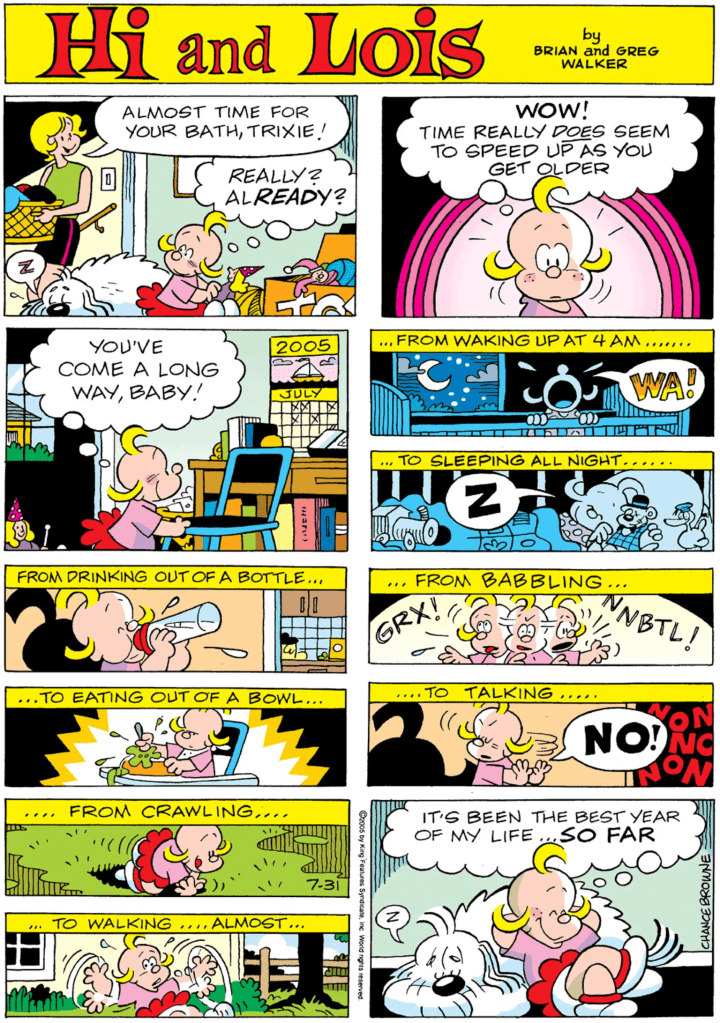

Throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, playwright August Wilson spent much of his time in diners and coffee shops in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, scrawling notes on napkins about the sights, sounds and working-class people of the historically Black neighborhood.

Pittsburgh was Wilson’s muse for his American Century Cycle, a landmark collection of 10 plays that span the decades of the 20th century and shine a light on the experiences—both good and bad—of Black Americans. Now, the city is paying homage to the influential late playwright with a permanent immersive exhibition called “August Wilson: The Writer’s Landscape” at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center, reports Joshua Axelrod for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Divided into 13 separate walk-through installations—10 of which focus on the plays in the Century Cycle—the 1,800-square-foot exhibition includes props, costumes and set pieces from Wilson’s productions, along with many of his personal items. Visitors can wander through Wilson’s home office or imagine him sipping a cup of coffee at Eddie’s, a diner he frequented.

Interactive video displays and audio clips also help tell the story of Wilson’s life and work. As Janis Burley Wilson, the center’s president and CEO with no relation to the playwright, tells the Post-Gazette, the playwright explored universal feelings and ideas through the lens of Black characters.

“The themes that he explores in his plays are love, betrayal, trust, hopes, dreams,” she says. “That’s really applicable to everyone. He’s an African American playwright who wrote about the African American experience, but it’s really the human experience.” Wilson was born Frederick August Kittel in 1945—the son of Frederick Kittel, a white German immigrant whom he never had much of a relationship with, and Daisy Wilson, a Black woman who cleaned homes and cared for him and his five siblings. After a teacher accused him of plagiarism when he was a teenager, the youth dropped out of school and began spending much of his time reading at the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. (Later in his life, the library awarded him the only high school diploma it ever issued in recognition of his contributions to literature.)

At age 20, he adopted his mother’s maiden name as his own and became August Wilson. He tried unsuccessfully to make a living as a poet before he moved to Minnesota and began writing plays in the late 1970s.

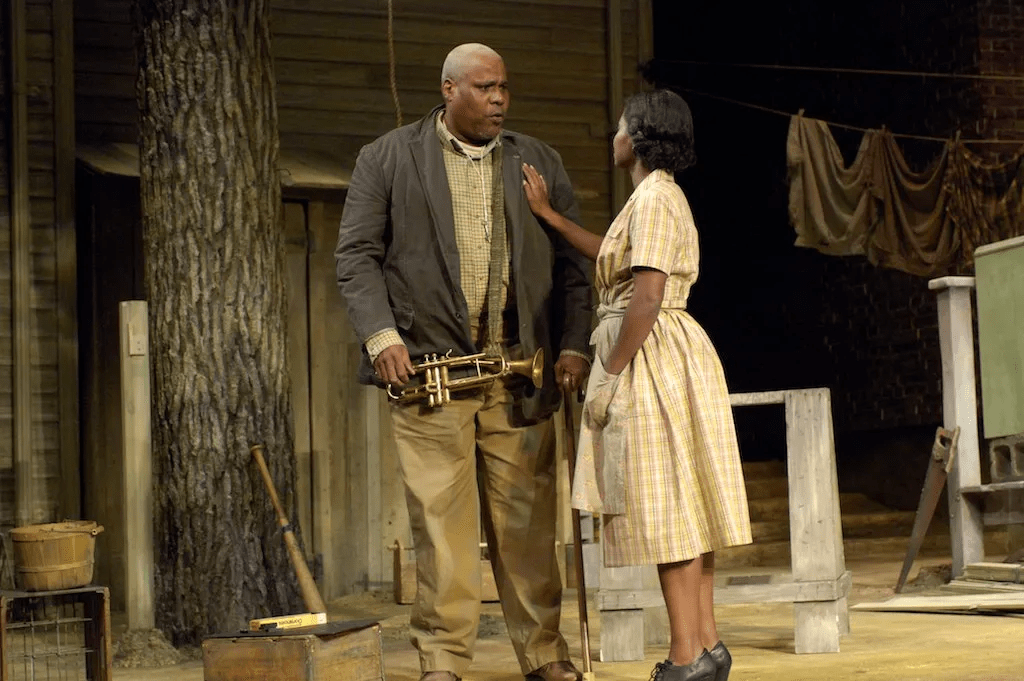

Bill Nunn (Gabriel) and Crystal Fox (Rose Maxson) perform in the August Wilson play Fences at The Huntington Theatre in Boston. The Huntington via Flickr under CC BY-SA 2.0

One of Wilson’s first plays, Jitney, landed him a fellowship at the Minneapolis Playwrights’ Center. His career took off from there. Wilson won a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony Award for Fences, the sixth play of the Century Cycle, which premiered on Broadway in 1987. He won a second Pulitzer for The Piano Lesson in 1990 and, in 2017, posthumously earned his second Tony Award, this time for Jitney. In total, he was nominated for Tony Awards for all nine of his plays that were produced on Broadway.

His work gave a voice to often-overlooked Black Americans, including mill workers, unlicensed cab drivers and trash collectors. Through these and other characters, Wilson adeptly explored the effects of decades of racism, but also the joys and triumphs of Black Americans. Thanks in large part to Wilson, Black theater artists “didn’t need permission to be a part of America,” Ruben Santiago-Hudson, an actor who has performed in and directed several of Wilson’s plays, tells NPR’s Bill O’Driscoll.

“With August Wilson, we are America,” Santiago-Hudson says. “Instead of Black life being in the periphery, he put Black people’s lives in … the center of what is Americana.”

Until now, Wilson’s namesake center, which opened in 2009, had no exhibition or display dedicated to the decorated playwright. It tapped Wilson’s wife Constanza Romero, an accomplished costume designer and artist in her own right, to curate the exhibition. On top of reviewing the many requests from producers who want to put on Wilson’s plays, Romero is also leading the charge to turn Wilson’s childhood home in Pittsburgh into an arts center.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0b/28/0b280ac8-521f-4773-82c4-56b5d4808927/8498210828_2187805c4a_o.jpg)

Wilson died of liver cancer in 2005, but his work remains timely and popular. In the last six years, Romero has helped produce award-winning film adaptations of her late husband’s plays Fences and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. (Viola Davis won the Academy Award for best supporting actress in Fences in 2017, while Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom won two Academy Awards in 2021: one for best costume design and another for best makeup and hairstyling.) Denzel Washington, who produced both films and directed and starred in Fences, has pledged to produce all 10 of the plays in the Century Cycle for HBO.

By exploring the country’s history through Black stories, Wilson’s plays have the power to help combat “the ongoing forces of systemic racism” that persist today, Romero told UC Santa Cruz Magazine’s Peggy Townsend in August 2021.

“What drives me right now is keeping his legacy alive and making sure his stories are still relevant and speak to the political climate of our time,” Romero told the magazine.

Sarah Kuta – Daily Correspondent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)

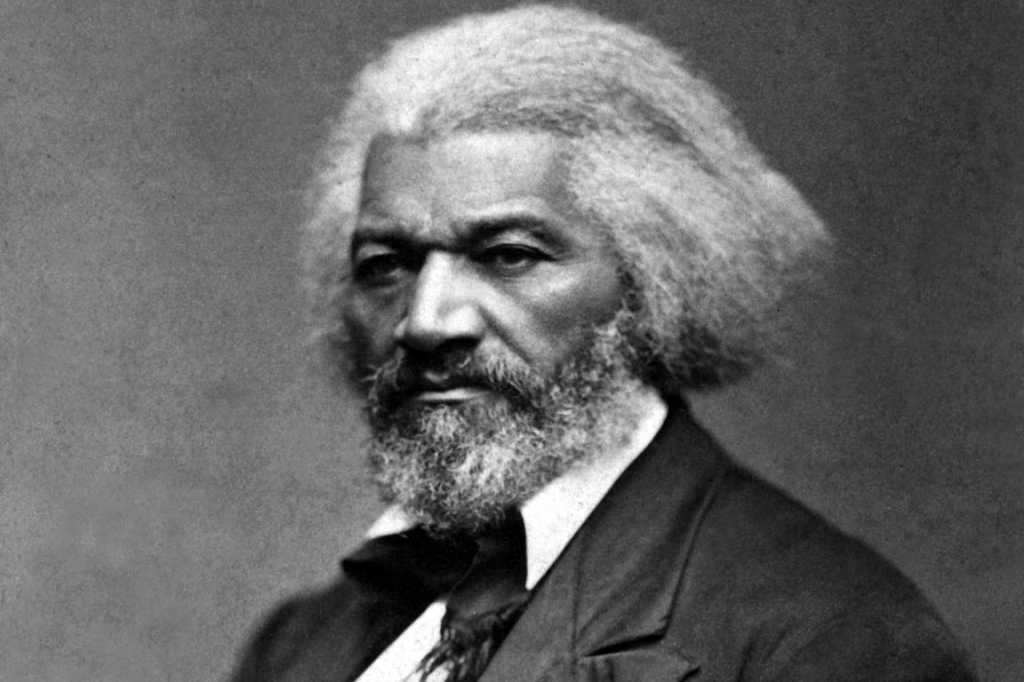

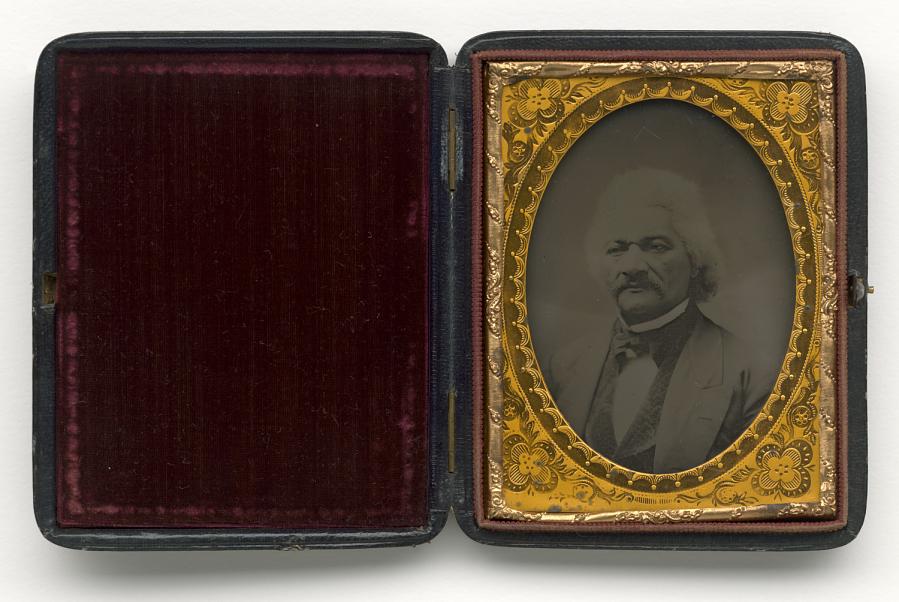

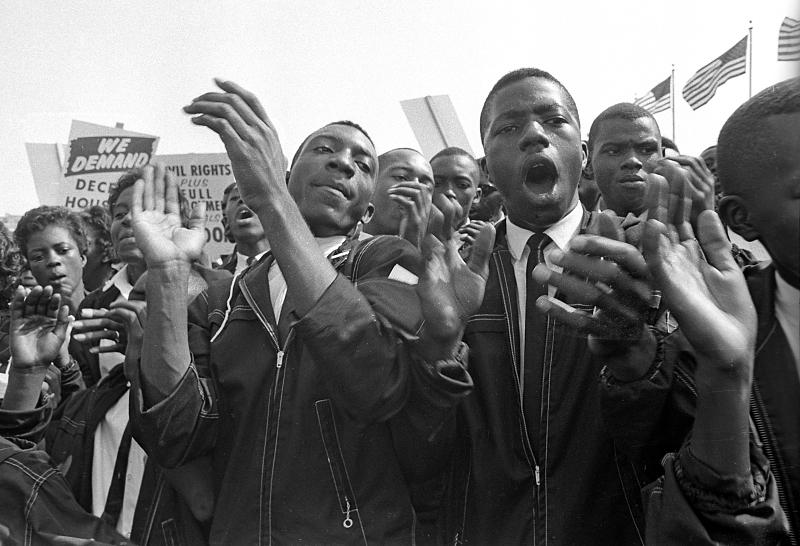

On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass gave a keynote address at an Independence Day celebration and asked, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Douglass was a powerful orator, often traveling six months out of the year to give lectures on abolition. His speech, given at an event commemorating the signing of the Declaration of Independence, was held at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York. It was a scathing speech in which Douglass stated, “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine, You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

In his speech, Douglass acknowledged the Founding Fathers of America, the architects of the Declaration of Independence, for their commitment to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness:”

“Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men, too, great enough to give frame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.”

Douglass stated that the nation’s founders were great men for their ideals of freedom. But in doing so he brings awareness to the hypocrisy of their ideals by the existence of slavery on American soil. Douglass continues to interrogate the meaning of the Declaration of Independence, to enslaved African Americans experiencing grave inequality and injustice:

“Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?”

We use the video player Able Player to provide captions and audio descriptions. Able Player performs best using web browsers Google Chrome, Firefox, and Edge. If you are using Safari as your browser, use the play button to continue the video after each audio description. We apologize for the inconvenience.

I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. Frederick Douglass“What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

“Would to God, both for your sakes and ours, that an affirmative answer could be truthfully returned to these questions! Then would my task be light, and my burden easy and delightful. For who is there so cold, that a nation’s sympathy could not warm him? Who so obdurate and dead to the claims of gratitude, that would not thankfully acknowledge such priceless benefits? Who so stolid and selfish, that would not give his voice to swell the hallelujahs of a nation’s jubilee, when the chains of servitude had been torn from his limbs? I am not that man. In a case like that, the dumb might eloquently speak, and the ‘lame man leap as an hart.’

But such is not the state of the case. I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

– Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852

National Museum of African American History and Culture