:focal(2736x1824:2737x1825)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ce/7c/ce7c4722-2c18-482d-9917-875797d5449c/gettyimages-1457707031.jpg)

McNeil and three other Black freshmen held a famous sit-in at Woolworth’s in 1960, which inspired peaceful protests across the country

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)

Sarah Kuta – Daily Correspondent

Joseph McNeil, one of the “Greensboro Four” who sparked nationwide demonstrations over segregated lunch counters in 1960, has died at age 83. The cause of death was Parkinson’s disease, per the New York Times’ Bernard Mokam.

To honor McNeil, North Carolina Governor Josh Stein ordered all state facilities to lower their United States and North Carolina flags to half-staff on September 13, the day funeral services will be held in Wilmington.

“Joseph A. McNeil’s legacy is a testament to the power of courage and conviction,” says Joseph McNeil Jr., one of McNeil’s children, in a statement shared with WGHP’s Emily Mikkelsen. “His impact on the civil rights movement and his service to the nation will never be forgotten.

McNeil was born in Wilmington in March 1942. After graduating from an all-Black high school, McNeil enrolled at the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina (now North Carolina A&T State University) in the fall of 1959.

During his first semester on campus, McNeil started talking with a handful of his fellow dorm-mates about taking a stand against segregation. McNeil’s desire to take action was further solidified when, while returning to campus after the holiday break, he faced discrimination at a bus station in Richmond, Virginia.

With support and funding from a handful of older Greensboro residents, McNeil and three classmates—Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr. (who later changed his name to Jibreel Khazan) and David Richmond—decided to take action.

On February 1, 1960, the four men sat down at the whites-only lunch counter at Woolworth’s in Greensboro. They tried to order coffee, but the waitress refused to serve them because they were Black. She called over the manager, who asked the four students to leave. But they stayed put.

Quick fact: What became of Woolworth’s

The restored Greensboro location of Woolworth’s was named a National Historic Landmark in late 2024.

They remained seated even after a police officer showed up, and as white customers yelled racial slurs at them. Eventually, the manager closed the store early and the four men went home.

They returned to the lunch counter over the next few days, bringing more and more classmates with them. By February 5, the peaceful sit-in had ballooned to hundreds of students, including white women from the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina (now the University of North Carolina at Greensboro).

All along the East Coast, protesters began picketing at various Woolworth’s locations, demanding that the five-and-dime chain store allow Black patrons to sit at the lunch counter and be served. By the end of March, the demonstrations had spread to 54 cities and included thousands of students, per the Times.

In May, the city of Nashville integrated its lunch counters. In late July, about six months after the first sit-in, the Greensboro Woolworth’s quietly desegregated its lunch counter. Four Black employees were the first to be served, according to History.com.

McNeil graduated with a degree in engineering physics in 1963. He went on to serve in the U.S. Air Force, working as a navigator on an aerial refueling plane during the Vietnam War.

He met and married Ina Brown while he was stationed in South Dakota. McNeil held numerous jobs over the course of his career, including as an investment banker, according to the Associated Press’ Gary D. Robertson. He also joined the Air Force Reserve, retiring in 2000 with the rank of major general.

Woolworth’s Greensboro location closed in 1993, but a section of the lunch counter was saved and is now on permanent display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. In 2010, the Smithsonian awarded the members of the Greensboro Four with the James Smithson Bicentennial Medal, which recognizes individuals who have made “distinguished contributions to the advancement of areas of interest to the Smithsonian.”

In a 2017 interview for the Smithsonian display, McNeil said the experience taught him the value of persistence and optimism. “I walked away with an attitude that if our country is screwed up, don’t give up,” he said, as reported by Smithsonian magazine’s Christopher Wilson in 2020. “Unscrew it, but don’t give up.”

Khazan is now the only surviving member of the Greensboro Four. Richmond died in 1990, followed by McCain in 2014.

McNeil and the other members of the Greensboro Four “inspired a nation with their courageous, peaceful protest, powerfully embodying the idea that young people could change the world,” says James R. Martin II, chancellor of North Carolina A&T State University, in a statement. “His leadership and the example of the A&T Four continue to inspire our students today.”

:focal(1050x750:1051x751)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/69/81/698163bc-17a8-4db6-b50f-9d867278cdeb/ballots_web.jpg)

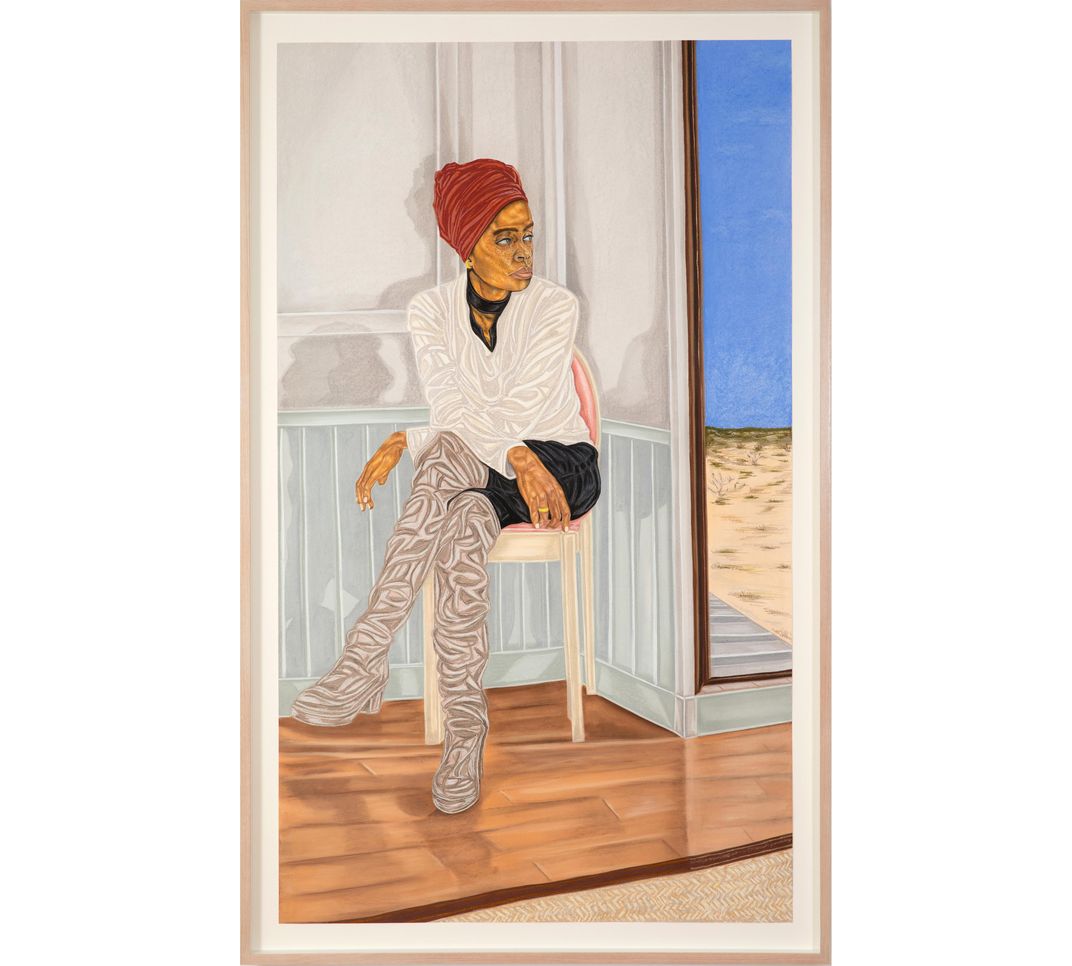

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8c/e1/8ce118db-d9a1-4ff2-b4c3-03b08516f1de/nov2024_i18_prologue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cc/d2/ccd243c3-2279-4be5-b1e4-9401c513c40e/untitled-2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/d4/15d45594-73e3-48bc-9938-868ac3b36d17/nov2024_i16_prologue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/fd/c3fdcc5e-dd6f-458f-941c-dc66fa44eb21/nov2024_i17_prologue.jpg)

:focal(830x548:831x549)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/34/ab349fad-84c6-403d-aedd-dbdbf8e7ebed/opener-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)