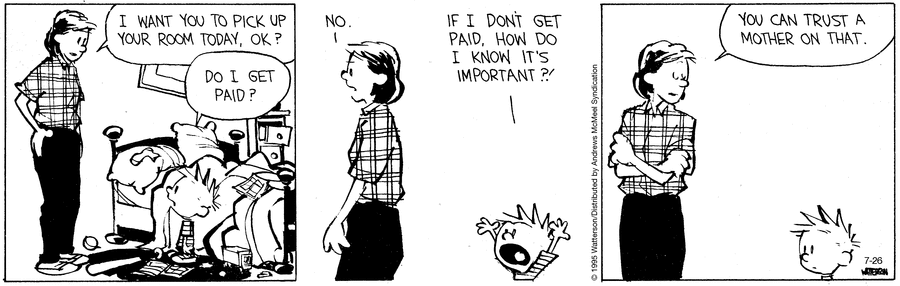

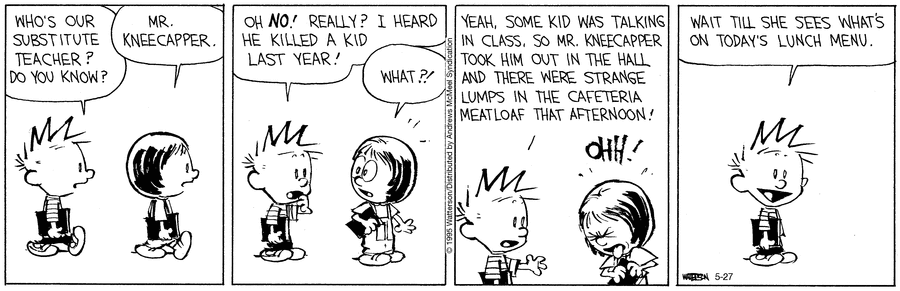

Comic Strips

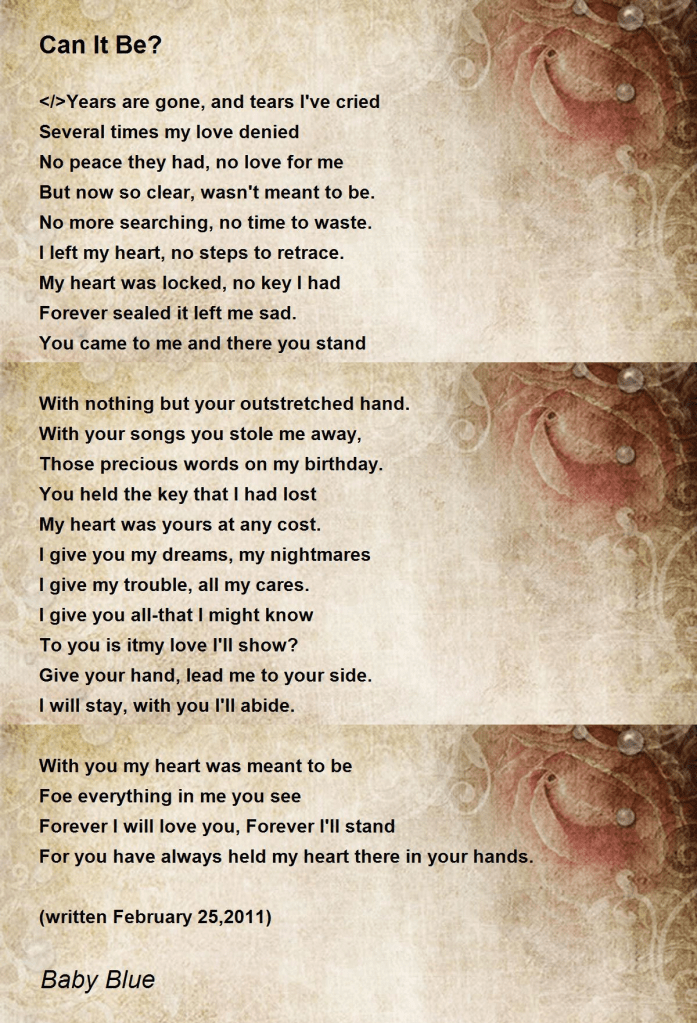

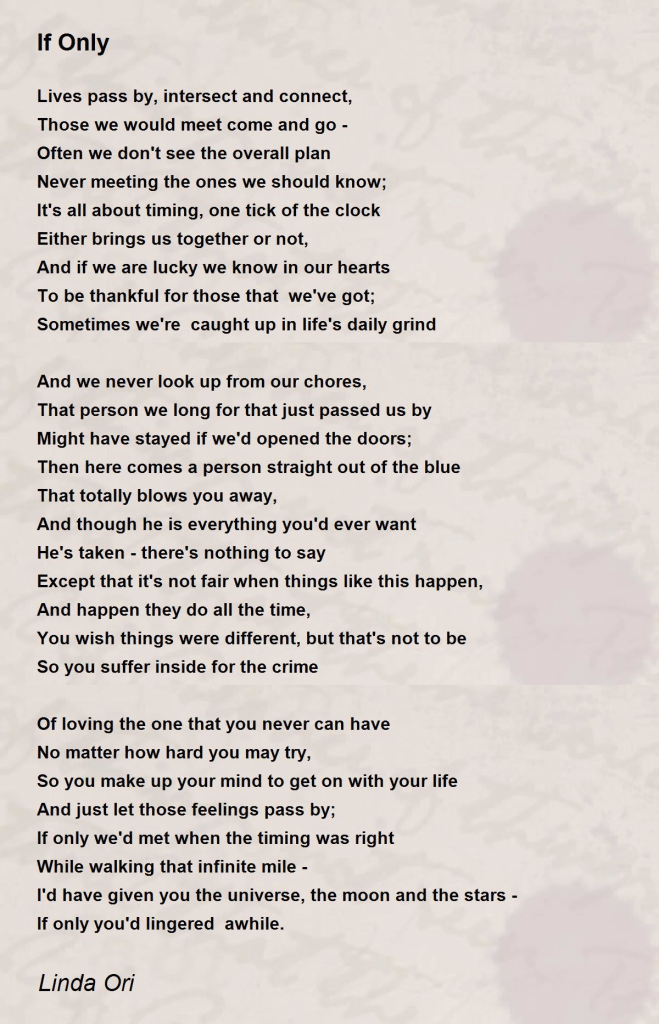

Poetry, Arts, Cooking, Communication, Culture and More!

:focal(1050x750:1051x751)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7d/2e/7d2e9be7-6fa4-4027-be32-6174aa2cd2b5/mar2025_e11_prologue.jpg)

When Citizen Kane premiered on May 1, 1941, it wasn’t at some historic Hollywood theater, or even at one of New York’s fancy movie houses. Instead, the film destined to become the most admired of all time opened more modestly, at a former vaudeville hall on Broadway. All glitzier plans had been scuttled by newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who believed, correctly, that the film was a thinly veiled indictment of him. Hearst banned his many newspapers from even mentioning Orson Welles’ filmmaking debut, and in many accounts, the magnate had offered a handsome bounty, worth more than the film’s budget, to purchase the negatives, simply for the pleasure of destroying it. Welles later said a Hearst minion had tried, unsuccessfully, to frame Welles by sending a 14-year-old girl to his hotel room. It was a full-on campaign to derail the career of the 25-year-old filmmaker before it had begun.

Thanks to Hearst’s boycott, Citizen Kane was a box office flop, losing the studio, RKO, at least $150,000, a bit more than $3 million today, even though many early reviewers were gobsmacked. The critic Bosley Crowther, writing in the New York Times, praised the outsize ambitions of writer-director-producer-star Welles, celebrating the young auteur for his brash style, which showed “more verve and inspired ingenuity than any of the elder craftsmen have exhibited in years.”

Equal parts bootstrap fable (think Horatio Alger) and tragedy (think Doctor Faustus), the movie tells the life story of Charles Foster Kane, who rises from a modest Colorado boarding house to the highest echelons of American power as a cocksure media magnate whose meaty fingers could tip the scale of world power—and whose cryptic last word before dying, “rosebud,” provides the mystery that drives the film. Yet Welles’ startlingly new approach to visual storytelling elevated the rags-to-riches template into high tragedy—and uncomfortable satire. Bucking convention at every turn, Welles skipped around chronology freely, using inventive dissolves and edits to move the viewer back and forth in time. The small touches were groundbreaking. One famous shot in the first minutes of the film, showing reflections in a smashed snow globe, anticipates the film’s grand themes of ambition and legacy and the cracked mirror of memory. Welles attributed these innovations to his own ignorance as a first-time filmmaker entering Hollywood from a career in theater and radio. “It’s only when you know something about a profession,” he told an interviewer, “that you’re timid or careful.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/9c/0d9c7c86-3a2a-4d01-9ba3-d2e85f01fd73/mar2025_e08_prologue.jpg)

After its unhappy opening in the United States, the film receded, until a detailed 1947 essay by the French critic André Bazin, who went on to co-found the iconic French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, hailed Citizen Kane as “a revolution in film language.” French critics and filmmakers championed the film, and Americans gave it another chance. It was released for a second time in the States in 1956, to a broader—and more appreciative—audience. By 1962, a survey of around 70 esteemed movie critics hailed it as the greatest movie ever made. It is also one of the most influential. In particular, Welles’ endless capacity for experimentation, combined with his bullheaded persona, was a central inspiration for the New Hollywood directors of the 1970s. “The one key element we learned from Welles was the power of ambition,” the director Martin Scorsese once said. “He is responsible for inspiring more people to be film directors than anyone else in the history of the cinema.”

In a tragic turn, Hearst’s hatred managed to do lasting damage to Welles professionally: The brilliant filmmaker and star found himself having to battle with studios for artistic control, often struggling to fund projects for the rest of his life, and never once made a movie that turned a profit in his lifetime. Welles once joked of his career: “Began at the top, and have been working my way down ever since.” The long shadow of Hearst’s curse has only deepened the sense of mystique around Welles’ most famous, and in some ways most enigmatic, movie.

One could argue that Welles has triumphed against Hearst in the battle of legacies; so the Hearst Estate seemed to admit in 2015, when it finally screened Citizen Kane at the magnate’s famously garish castle in San Simeon, California. Regardless, the film’s scandalous backstory remains an essential component of its all-American greatness. In her 1971 book-length New Yorker essay about the film’s production, critic Pauline Kael contended that Hearst ultimately became “the victim of his own style of journalism.” That is to say, Welles had matched Hearst in his capacity for sensationalism, crafting a brilliant feature film that doubled as its own sort of yellow journalism. In this way, Citizen Kane was not only a high-water mark for the American cinema circa 1941; it also anticipated reality television, the celebrity-flogging of TMZ, plus other, arguably more execrable, trends in American entertainment and public life. It is a towering artistic achievement, shot through with the inky grease of tabloid sleaze.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/37/633702ad-8278-4c75-8d4d-b08f66e0ab4d/dbeb3c-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

Maya Wei-Haas – Reporter

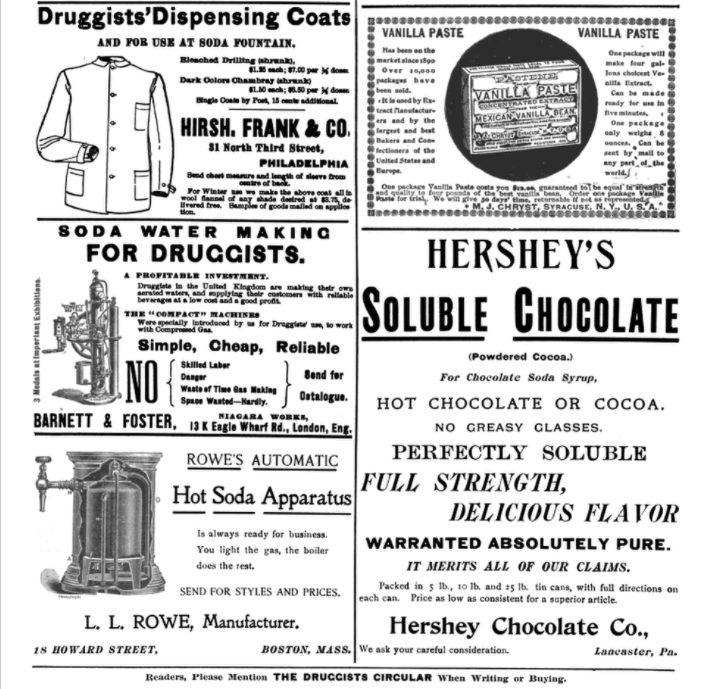

At first glance, nothing seems particularly odd about the December 1896 edition of The Druggists Circular and Chemical Gazette, a catalog of products that any self-respecting pharmacy ought to carry. But look closer: Hiding among medical necessities like McElroy’s glass syringes and Hirsh Frank & Co’s lab coats, you’ll find some more curious finds—including Hershey’s cocoa powder.

“Perfectly soluble,” boasts the ad in bold, capital lettering. “Warranted absolutely pure.” It reads as if it was peddling medicine—and in fact, it sort of was.

Druggists of the day often used the dark powder to whip up a syrup sweet enough to mask the flavor of objectionable remedies, explains Stella Parks, a pastry chef with the food and cooking website Serious Eats. Parks happened upon these vintage advertisements while she was researching her new book, BraveTart: Iconic American Desserts, which features lesser-known histories of our favorite sweet treats.

The Hershey’s ad intrigued her. “What in the world are these guys doing advertising to druggists?” she recalls wondering at the time. By digging into the history and tracking down more pharmaceutical circulars and magazines, she discover the rich history of chocolate syrup, which began not with ice cream and flavored milk—but with medicine.

Our love of chocolate goes back over 3,000 years, with traces of cacao appearing as early as 1500 B.C. in the pots of the Olmecs of Mexico. Yet for most of its early history, it was consumed as a drink made from fermented, roasted, and ground beans. This drink was a far cry from the sweetened, milky stuff we call hot chocolate today: It was rarely sweetened, and likely very bitter.

Still, the roughly football-sized pods that cradled the beans were held in high esteem; the Aztecs even traded cacao as currency. Chocolate didn’t become popular overseas, however, until Europeans ventured into the Americas at the end of the 15th century. By the 1700s, the ground beans were avidly consumed throughout Europe and the American colonies as a sweetened, hot drink that was vaguely reminiscent to today’s hot cocoa.

At the time, chocolate was touted for its medicinal properties and prescribed as treatment for a range of diseases, says Deanna Pucciarelli, a professor of nutrition and dietetics at Ball State University who researches the medicinal history of chocolate. It was often prescribed for people suffering from wasting disease: The extra calories assisted in weight gain, and the caffeine-like compounds helped perk patients up. “It didn’t treat the actual illness, but it treated the symptoms,” she explains.

Yet for pharmacists, it wasn’t only the supposed health benefits but also the rich, velvety flavor that held such appeal. “One thing about medicines, even going way back, is that they are really bitter,” says Diane Wendt, associate curator of the division of medicine and science at Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Many medications were originally derived from plants and fall in a class of compounds known as alkaloids, which has an acrid, mouth-puckering flavor. The first of these alkaloids, isolated by a German chemist in the early 1800s, was none other than morphine.

Chocolate, it turns out, effectively covered the toe-curling taste of these foul flavors. “Few substances are so eagerly taken by children or invalids, and fewer still are better than [chocolate] for masking the taste of bitter or nauseous medicinal substances,” according to the 1899 text, The Pharmaceutical Era.

It’s unclear exactly when pharmacists first combined cocoa powder and sugar to brew the sticky syrup. But its popularity was likely helped along by the invention of cocoa powder. In 1828, Dutch chemist Coenraad J. Van Houten patented a press that successfully removed some of chocolate’s natural fats, reducing its bitter flavor and making it easier to dissolve with water. Still, the result wasn’t exactly the “same kind of smooth mellow chocolate we have now,” says Parks; to make it palatable, pharmacists would mix cocoa powder with at least eight times more sugar than chocolate.

The popularity of chocolate syrup exploded in the second half of the 19th century, coinciding with the golden age so-called patent medicines. These are named after the “letters of patent” the English crown awarded to inventors of supposedly curative formulas. The first English medicine patent was awarded in the late 1600s, but the name later came to refer to any over-the-counter drugs. American “patent medicines” went by the same name, but were not typically patented under this system.

Patent medicines emerged at a time when public need for treatments and cures outpaced medical knowledge. Many of these “cures” did more harm than good. Often marketed as cure-alls, the concoctions could contain anything from pulverized fruits and veggies to alcohol and opioids. At the time, the common use of these addictive substances in remedies was legal; regulation didn’t come about until the 1914 passage of the Harrison Narcotic Act.

One popular remedy featuring tincture of opium as its active ingredient was Stickney and Poor’s Paregoric. This syrup was marketed as a treatment for many ills, and given to cholicky infants as young as five days old. “Remedies” like this weren’t completely ineffective. The inclusion of narcotics and alcohol in the cures did indeed give customers temporary relief from illness—and, more sinisterly, their addictive nature kept them coming back for more.

The boom of factory mass production in the 1900s brought with it the rise of easy-to-swallow medical pills. But before that, “pill making by hand is pretty labor intensive,” says Wendt. “To actually make a pill of a certain dose—to mix it up and cut the pills, and roll the pills, and dry the pills, and coat the pills—that’s a pretty lengthy process.” That’s why, during this time, medications were mostly served up in liquid or powder form, says Wendt.

Druggists would mix each liquid remedy with a base of sugary flavored syrups, like chocolate, and take it either by the spoonful or mixed into a beverage, says Wendt. Alternatively, powders could be directly poured into your refreshment of choice. The base for these medicinal drinks could be anything from plain water to tea to a couple fingers of whiskey. But over the course of the 1800s, one particular drink was gaining popularity as a medicine masker: carbonated water.

Not unlike chocolate, soda water was initially considered a health drink in its own right. The carbonated beverage mimicked the mineral-rich waters bubbling up in natural springs that had become known for its curative and healing powers. Soda became a truly widespread phenomenon in America around the turn of the century thanks to the pharmacist Jacob Baur, who invented the process necessary to sell tanks of pressurized carbon dioxide.

Part health drink, part delicious treat, sweetened carbonated water began spreading like wildfire in the form of soda fountains, Darcy O’Neil writes in his book Fix the Pumps.

Syrups became ever more popular to keep pace with the soda craze. Many of these flavors are still common today: vanilla, ginger, lemon and, of course, chocolate. By the late 1800s hardly a pharmacist publication went without some mention of chocolate syrup, Parks writes in Bravetart. And hardly a drug store went without a soda shop: Soda fountains served as a lucrative side business for druggists and pharmacists who commonly struggled to make ends meet, says Parks.

At the time, carbonated concoctions were largely still seen as cures. “Soda is an excellent medium for taking many medicines,” according to the 1897 book, The Standard Manual of Soda and Other Beverages. “For example, the best method of administering castor oil is to draw a glass of sarsaparilla soda in the usual manner and pour in the requisite amount of oil.” (Sarsaparilla, a flavor derived from the root of a tropical vine, is still used today in some root beer variants.)

One example still very much available today is Coca Cola: Originally mixed up with cocaine, the fizzy drink was touted it as a healthful stimulant to revive the brain and body.

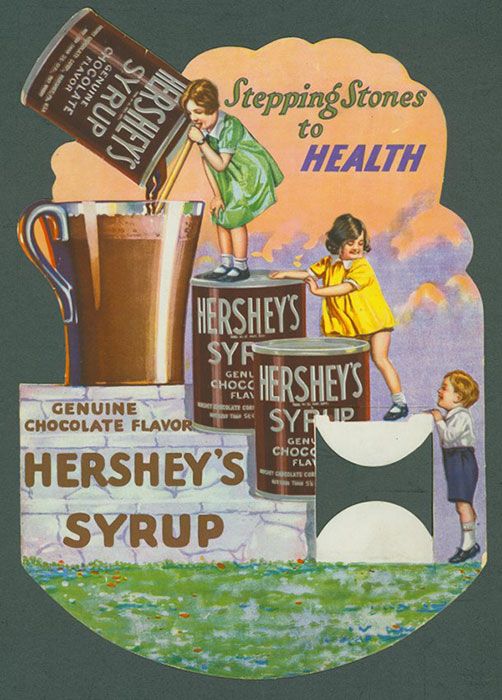

At the turn of the century, however, chocolate syrup began to shift from treatment to treat. “It just seemed to naturally segue into all the ice cream [desserts] that pharmacists had to keep on hand just to stay afloat,” says Parks.

A fortuitous mix of events helped elevate the state of chocolate to commercial confection. First, in the early 20th century, concerns over false health claims and downright dangerous cures helped lead to the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, which required druggists to disclose the remedy ingredients with clear and accurate labels. Similarly, a clamp down on American patent medicines may have further driven the chocolatey transition.

At the same time, other forms of chocolate were gaining traction as confections in their own right. As the industrial revolution ushered in machinery that took over the time-intensive process of turning cacao to cocoa, prices began to fall, explains Pucciarelli. “It all comes together,” she says. “The price of manufacturing drops, the price of sugar drops, and then you have [chocolate] bars.”

In 1926, Hershey’s began marketing pre-mixed chocolate syrup in both single and double strength varieties for commercial businesses. The cans were shelf stable, meaning druggists (and soda jerks) didn’t need to continually mix up new batches. By 1930, both Hershey’s and other chocolate companies like Bosco’s had begun marketing chocolate syrup for home use.

The rest is sweet, sweet history. These days, despite many modern claims of health benefits—some founded and some unfounded—chocolate is considered more confection than cure. Chocolate accounts for the “vast majority” of the $35 billion confection market in the United States, according to the National Confectioners association.

Yet the use of a sweet cover for medications remains isn’t completely dead. You can find sweetness masking medicine in many forms, from cherry cough syrup to bubblegum-flavored amoxicillin. It seems Mary Poppins was right: A spoonful of sugar—or in this case, chocolate—really does help the medicine go down.