Poetry

Poetry, Arts, Cooking, Communication, Culture and More!

:focal(1058x817:1059x818)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/80/fd/80fd6fa3-5924-4d4d-9e87-4696de93968e/gg_3548_201401_nr_cd_presse.jpg)

Ella Feldman – Daily Correspondent

Some of history’s greatest artists weren’t discovered until after their time. Johannes Vermeer wasn’t celebrated as a 17th-century Dutch master until art historians rediscovered his work in the 1860s. Vincent van Gogh only became world-famous years after his death in 1890.

But it’s taken more than three centuries for Michaelina Wautier, a 17th-century female Flemish Baroque painter and the subject of a new exhibition at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, to be recognized as an old master.

“Michaelina Wautier, Painter” marks the first time in history that so many of Wautier’s paintings have been displayed together. The exhibition features almost all of her known works, including 29 paintings, a drawing and a print, per ARTnews’ Leigh Anne Miller.

The collection’s crown jewel is The Triumph of Bacchus, a large-scale oil painting of half-robed bodies surrounding the god of wine. The piece was rediscovered in 1993 by Belgian art historian Katlijne Van der Stighelen in the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s archives, per the Guardian’s Philip Oltermann. In town for a conference, Van der Stighelen was visiting the museum to look at a different painting by Anthony van Dyck when the work of revelry caught her eye.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes,” Van der Stighelen tells the Guardian. “I really know my way around Flemish paintings from the 17th century, but when I saw this picture I could not match it with anything I knew.”

The museum’s archivist told Van der Stighelen that the painting was thought to have been the work of a woman, which set the art historian off on a three-decade journey to learn more about the artist’s identity. In 2018, she curated “Michaelina: Baroque’s Leading Lady” at the Museum aan de Stroom in Antwerp, Belgium, which helped raise the forgotten artist’s profile.

Van der Stighelen contributed to the catalog for “Michaelina Wautier, Painter,” which was curated by Gerlinde Gruber, per the New York Times’ Valeriya Safronova.

In the past, Wautier’s paintings have often been attributed to her male contemporaries, including her brother, Charles Wautier. That’s despite the fact that around half of her 35 surviving works bear her signature.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a8/d7/a8d776fc-db61-4b05-95bd-678f11b2222e/michaelina_wautier_self_portrait_private_collection_image_from_mfa_presse.jpg)

“She’s a Flemish Baroque painter, a woman, and for many years people didn’t believe that the canvases done by her were by her,” Jonathan Fine, the Kunsthistorisches’ director general, tells the Times.Report This Ad

Very little is known about Wautier’s life, as very few primary documents about her survive. Instead, researchers have had to rely on the paintings themselves. That includes analyzing her works via X-rays and infrared and ultraviolet light, per the Times.

Historians think the artist was born in Mons, Belgium, in 1604 and began her artistic career when she was in her 30s.

In Wautier’s time, women were not allowed to enroll in art academies, but experts say her work is so advanced that she must have received some kind of formal training, the Guardian reports. It’s possible that training came from her brother, who was also a painter.

The Triumph of Bacchus makes Wautier the first known woman to have made a life-size painting of a nude man. It also suggests that she was able to study nude male bodies up close, perhaps in her brother’s studio.

“When you look at Wautier’s paintings, it’s immediately evident that she knew what the body was,” Van der Stighelen tells the Guardian. “When you look at the variety of ages, skin colors and hair textures in the Bacchus painting, it’s impossible that she worked purely off plaster copies. She must have had the opportunity to draw and paint from life.”Report This Ad

On the far right of the painting, a woman in a pink garment looks directly at the viewer, with one of her breasts exposed. Some scholars think that Wautier based this figure on herself.

“She was really bold,” Kirsten Derks, an art historian at the University of Antwerp who has studied Wautier for years, tells the Times. “She included a self-portrait in that painting with her boob hanging out. I don’t know of any other artist who would dare to do that.”

Another highlight of “Michaelina Wautier, Painter” is the Five Senses series. Across five paintings, Wautier depicts young boys using their senses—sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch. The collection also includes a detailed painting of a colorful flower garland and a self-portrait of the painter by her easel.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/69/01/6901456d-8a63-46f3-a481-dc3949f47945/mwautier_5sinne_schmecken_photograph__c__2025_museum_of_fine_arts__boston_5113_small.jpg)

Wautier is one of many female artists whose contributions have been overlooked throughout history. Another new exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. spotlights some of those artists, including Johanna Koerten, Judith Leyster and Clara Peeters.

But the size, breadth and artistry found in Wautier’s paintings make her work unique.

“For female Baroque artists to work on this scale and with this variety of subjects is completely unseen,” Van der Stighelen tells the Guardian. “You had excellent women artists at the time painting flowers or still lifes, but in general they were much smaller than those produced by men, largely due to the fact that they didn’t have their own workshops. Wautier is a complete exception to the rule.”

“Michaelina Wautier, Painter” is on view at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna through February 22, 2026.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/26/42/26421b5e-13cf-4629-aa87-a03b21d3b487/title_page_chapter_8_holiday_celebrations_rituals_and_menus_copy.jpg)

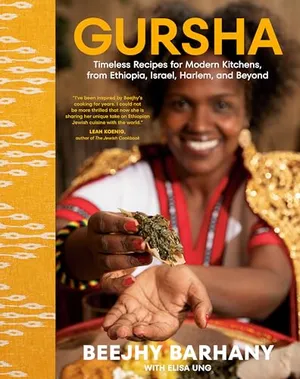

With a café in New York City and a new cookbook, Beejhy Barhany is bringing the stories and flavors of Ethiopian Jews to the States

“The base of Ethiopian cuisine as a whole is very much Jewish, more than anything else,” says Beejhy Barhany. Clay Williams

Andrea Cooper – Freelance writer

Delicious as they may be, matzo ball soup, challah, brisket and other Ashkenazi Jewish favorites will not be at the table when Beejhy Barhany celebrates Rosh Hashana this month.

The chef and owner of Tsion Cafe in Harlem, one of the few Ethiopian Jewish restaurants in the United States, suggests a Jewish New Year menu of beg wot, a lamb stew brightened with the Ethiopian spice blend berbere and ground, roasted korarima, akin to cardamom. For sides, she recommends dubba wot, a lush pumpkin stew with date honey, and a salad dotted with black-eyed peas, tomatoes, barley and arugula. Dabo, a spiced whole wheat bread, can soak up all the flavors. She’d top the feast off with ma’arn tzava cake, which mingles sweetness from honey with a slight tang from Ethiopian coffee extract.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3a/ed/3aed17ec-9b52-4c2b-a701-9d8581666b84/beejhy_barhany_c_clay_williams_copy.jpg)

Barhany, who was born in Ethiopia and grew up in Israel, is the author, with Elisa Ung, of a new cookbook,Gursha: Timeless Recipes for Modern Kitchens, From Ethiopia, Israel, Harlem and Beyond—the first major title to share Ethiopian Jewish food with home cooks. Gursha, in Amharic, one of the primary languages in Ethiopia, refers to the Ethiopian tradition of feeding others a mouthful by hand to show affection and respect.

“The base of Ethiopian cuisine as a whole is very much Jewish, more than anything else,” says Barhany, given that people practiced Hebraic traditions in Ethiopia prior to the arrival of Christianity in the fourth century.

Some of Tsion Cafe’s Black customers are surprised to learn that Barhany’s cuisine is Jewish. Other Jewish customers are surprised to meet a Jew from Africa. To these folks, Barhany says, “We Ethiopian Jews never knew of the existence of white Jews. We always thought we were the only ones, and white Jews thought they were the only ones.”

It’s unclear exactly how and when Jews arrived in Ethiopia. One theory is from the Midrash Rabbah, a set of Jewish commentaries and stories about the Torah written over at least eight centuries. It describes how Moses fled to Ethiopia, then known as Cush, following his killing of an Egyptian who was beating a Hebrew. Moses reigned there for 40 years and married an Ethiopian woman. He later returned to Egypt to lead the exodus of the Jews.

A joyous celebration of Ethiopian Jewish cuisine: more than one hundred accessible and healthy recipes, stories, and traditions from the intersection of the African and Jewish diasporas.Buy Now

A second account, in the Kebra Nagast, a 14th-century book venerated as the national epic of Ethiopia, recalls a tale about Makeda, the queen of Sheba. She visited King Solomon at his court and later had a son with him, Menelik, who became the first emperor of Ethiopia. The story holds that Menelik took the original Ark of the Covenant, the gold-plated wooden chest containing the tablets from which God delivered the Ten Commandments to Moses at Mount Sinai, from Israel to Ethiopia. According to Ethiopian tradition, it is currently housed in the Church of St. Mary of Zion in Aksum, protected by a monk with no one else permitted to view it.

The third theory suggests the tribe of Dan resettled in Ethiopia following the fall of the First Temple, a center of worship in ancient Israel, in the sixth century B.C.E. One former Sephardic chief rabbi of Israel, Ovadia Yosef, cited this argument when he granted permission for Ethiopian Jews to make aliyah, or immigrate to Israel and become citizens, in the 1970s under the provisions of the 1950 Law of Return. The law allows Jewish people with one or more Jewish grandparents and their spouses to move to Israel and gain Israeli citizenship.

Ephraim Isaac, director of the Institute of Semitic Studies in Princeton, New Jersey, says the historical entry of Jews into Ethiopia also has a non-biblical explanation: economics. A thriving trade of spices and, later, silk existed among Israel, Rome, Greece, India and China. Traders crossed through Ethiopia and used the ancient port of Adulis (now part of Eritrea), beginning in the late second century B.C.E. Trade along the Red Sea, including in Yemen, led to the development of Yemenite Jewish communities. The Hebrew Bible references ancient Israelites eating coriander and cumin, prized spices in Ethiopian Jewish cooking.

“The presence of Jews in Ethiopia goes back to biblical times,” says Isaac, an Ethiopian Yemenite Jew and the first faculty member hired for Harvard University’s Department of African and African American Studies in 1969. “With all due great respect, the presence of Jews in Poland is more surprising to me than the presence of Jews in Ethiopia.”

Estimates of the number of Ethiopian Jews still living in Ethiopia are hard to come by, in part because some opted to convert to Christianity, and some were forced to convert, in the 19th and 20th centuries, due to pressure from Christian missionaries. From 1974 to 1991, Ethiopia’s civil war, which pitted the country’s Marxist government against multiple insurgent groups, brought civil unrest and violence, later coupled with famine, to the Jewish community.

Ethiopia’s communist government banned Jews from leaving the country in the 1980s. Some escaped and left covertly for Israel via Sudan through several Israeli military operations, totaling about 23,000 emigrants. The latest, 1991’s Operation Solomon, later set a world record for the number of passengers—estimated at 1,088—on a commercial flight, including two babies born en route. The airline had removed the plane’s seats to accommodate more people.

Today,168,000 residents of Israel are of Ethiopian descent, the vast majority of whom are Jews. According to Barhany, a few thousand Ethiopian Jews make their home in the United States.

“It’s often told as a story of rescue, but it’s really important to emphasize the agency of the Ethiopian Jewish community,” says Shayna Weiss, senior associate director of the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies at Brandeis University. “There had been activists fighting for the ability to be recognized as a formal Jewish community to be able to immigrate.” They were, she stresses, “active participants in their own destiny.”

The journeys of Ethiopian Jews, Barhany included, helped spread their foods and flavors beyond Africa.

Four-year-old Barhany and her family fled their home in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia in 1980 with several hundred others in a caravan. They traveled by land, in an exodus organized by her cousin to Sudan, where they would then depart for Israel. The group had packed flaxseed, teff, coffee, chickpeas and honey for their subsistence, but locating water was a constant challenge. They would pause their trek for the Sabbath and bake kita, a flatbread. They ended up living in a Sudanese village with other Ethiopian refugees for several years before relocating to Israel.

Two generations of Ethiopian Jews living in Israel have now left their mark on the culinary scene, helping contribute to the rise of vegan food in the country. Vegetables figure prominently in Ethiopian cuisine, and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church permits only vegan meals on fasting days, such as the 40 days of advent. Ethiopian Jews are also known for making vegetable dishes. “To go to Israel today is to have babka next to berbere next to bourekas,” says Michael Twitty, a culinary historian and the author of Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew. “It’s no different than the concept of American food, where all of a sudden a red sauce in Italy becomes Sunday gravy in America.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/09/42095bd0-f756-4461-9986-013db4a4e675/hanukkah_copy.jpg)

Ethiopian food and Ethiopian Jewish food is basically inextricable, Barhany explains. The foundations of the former derive from the latter.

A clear example of that is berbere, a classic Ethiopian spice. What’s in it? That varies as much as cooks themselves. Barhany begins hers with a hefty amount of paprika and cayenne pepper, then laces in korarima, ground ginger, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, fenugreek and more. Stews are a central element of the cuisine, frequently built on kulet, a thick, fragrant sauce with tomato paste, onions, korarima, garlic, ginger and lots of berbere.

Misir wot, a comforting red lentil stew familiar to diners at Ethiopian restaurants, has an ancient Hebraic reference in the biblical story of brothers Esau and Jacob. “Esau came from the field, had an exhausting day, and he’s smelling this delicious stew that his brother Jacob was cooking,” Barhany says. Esau gave up his birthright, the story goes, in exchange for this rich meal.

Another favorite dish among Ethiopians, doro wot, or chicken stew, might be served on the Sabbath or at weddings. “Cutting up a whole chicken for doro wot is among the first skills that Ethiopian Jewish mothers teach their daughters,” Barhany writes in Gursha. Ethiopian Jews traditionally celebrate the Sabbath with readings from the Orit, a version of the Hebrew Bible that includes the five books of Moses plus the books of Joshua, Judges and Ruth, written in an ancient semitic language called Ge’ez.

Observant Ethiopian Jews don’t eat the country’s hallmark raw or very lightly cooked beef dishes, such as kitfo, a mix of raw ground beef, spices and niter kibbeh, or spiced butter, because of the Torah’s prohibition against mixing meat and milk.

Twitty is among the creative cooks devising American Jewish meals with Ethiopian flavors. He’s used berbere in brisket, fried chicken, greens, rice and black-eyed peas.

“Jewish food and Black food crisscross each other throughout history,” he writes in Koshersoul. “Both are cuisines where homeland and exile interplay.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e1/1a/e11a4a02-4330-49b7-8fed-52ae5747b38e/kita_-_kicha_-_flatbread_for_a_journey_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ed/05/ed051226-dbbc-4675-9448-c4de4a87cac5/gomen_-_hamli_-_braised_collard_greens_copy.jpg)

Twitty sees parallels between Ethiopian Jewish foodways and the cuisines of other African cultures that focus on a starch accompanied by soups and stews. Ingredients such as “okra, field peas, melons, teff, enset,” he says, “these are things which have resonance in the whole canon of African eating, because they’re part of that Upper Nile Valley agricultural system.”

As for any connections among Ethiopian Jewish cookery and the cuisines of Ashkenazi, Sephardi or Mizrahi Jews, Twitty notes that bread is central to them all, including tandoori bread in Central Asia and India, jachnunand malawach in Yemen, bejma in Tunisia, and injera in Ethiopia. He suspects Ethiopian and Yemenite dishes are the closest to what Jews ate in biblical times.

Barhany honors these connections at her vegan and kosher café in Harlem. One highlight of her menu is the portabella tibs, a sauté with mushrooms, tomatoes, fresh herbs and the Ethiopian hot sauce called awaze. The chef prepares her version of the spicy condiment with jalapenos, garlic, ginger and cilantro. The “Mama Africa” entrée combines jollof rice, black-eyed peas cooked in coconut milk, plantains and beets with a tahini, cilantro and lime sauce. In Gursha, she shares her recipes for schnitzel, shakshuka, Yemenite chicken soup, and collard greens and cabbage bourekas, to name just a few.

Barhany’s restaurant space was previously the site of Jimmy’s Chicken Shack, where jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker, comedian Redd Foxx and even Malcolm X once worked. She describes Tsion Cafe as a place of Pan-African love and Black Israeli pride.

“As a multicultural person, I have the ability to facilitate dialogue and understanding,” Barhany says, between two minorities—Jews and African Americans—who have been persecuted for hundreds of years. “Why not come together, amplify the story and unify? That’s been my core value.”