The creatures, which ranged in size from that of a fox to more than 50 feet long, divided their time between the coast and the water

The story of whales did not begin in the seas. For millions of years before beasts like the sinuous Basilosaurus lived full time in the ocean, the shorelines and estuaries of prehistoric Earth were filled with amphibious whales that more closely resembled otters and crocodiles than humpbacks. The first whales walked. Paleontologists have been pondering whale origins since the late 19th century. They knew that whales evolved from land-dwelling ancestors because of vestiges of hind limbs sometimes found in whale skeletons and other anatomical clues held in common with terrestrial mammals. Who those ancestors were, and how the transcendent evolutionary change from land to water occurred, was unclear. But since the 1970s paleontologists have found a vast array of early whales. The fossil finds have indicated that whales are artiodactyls—members of the hoofed mammal group that includes hippos and cows—and that aquatic whales as we know them represent one offshoot of a diverse array of early, semi-aquatic whales that evolved in the shallows. This list offers a fossil highlight reel of some of these beasts.

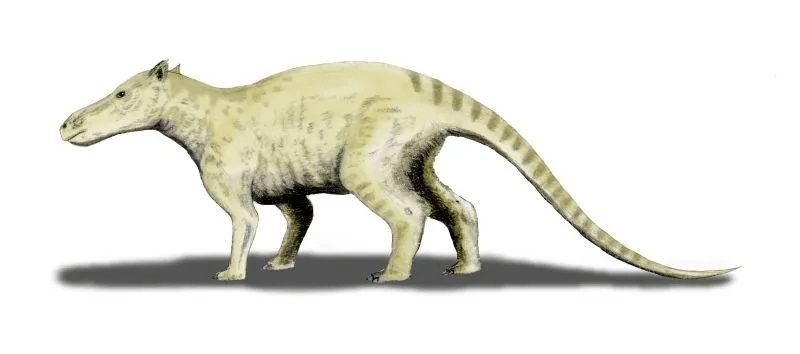

Pakicetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2e/e9/2ee97182-f30b-4ab1-a485-5b1421483c8e/pakicetus_bw.jpg)

If you were to visit the shores of prehistoric Pakistan about 50 million years ago, you might see a vaguely dog-like mammal trotting along the sand. The Labrador retriever-size creature was Pakicetus, one of the earliest known whales.

At a glance, Pakicetus doesn’t look like it would be able to do much more than doggy paddle. But at least two features indicate that this early whale spent a significant amount of its time swimming. The eyes of Pakicetus are relatively high on the mammal’s head, similar to alligators and crocodiles that peek their eyes and noses out of the water to watch the shore. More importantly, the bones of Pakicetus are relatively dense—a condition paleontologists know as osteosclerosis. The bones of Pakicetus, in other words, were a little heavier than those of other mammals of comparable size and acted as ballast to help the carnivore achieve neutral buoyancy in the water—and put more energy toward swimming than staying submerged.

Ichthyolestes

Paleontologists began finding early whales before they knew what they were looking at. In 1958, paleontologists studying fossil teeth found in the 50-million-year-old rock around Ganda Kas, Pakistan, thought that the choppers were unusual enough to signify a previously unknown fossil mammal they called Ichthyolestes, the “fish thief.”

Further explorations in the area eventually turned up more parts of the Ichthyolestes skeleton, and by the 21st century the animal was recognized as a fox-size relative of Pakicetus. The early whale still had hips fused to the spine and ankle bones that looked like those of its land-dwelling relatives, but its bones were so dense that running fast on land would have risked breaking them. Like its close relatives, Ichthyolestes lived around river mouths and estuaries, perhaps pushing off the bottom of shallow bodies of water as it searched for fish to eat.

Ambulocetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b0/2b/b02bdfd7-1049-474f-a722-453d0a04b9e0/ambulocetusnatanspisa.jpeg)

Of all the early whales uncovered by paleontologists, none has a toothy grin quite like Ambulocetus. The 48-million-year-old whale had a long snout full of sharp, blade-like teeth, well suited to nabbing fish and perhaps grabbing unwary small creatures from the shores of prehistoric Pakistan’s estuaries.Report This Ad

Ambulocetus was a much stronger swimmer than its predecessors like Pakicetus. The mammal’s body is much more otter-like, and paleontologists expect that Ambulocetus swam by undulating its spine up and down while using its paddle-like hind feet for an extra push. This swim stroke was a predecessor to the way modern whales flick their broad tail flukes up and down to push themselves through the water. While on land, Ambulocetus could support its own weight on its limbs but was not a runner like a wolf. The large, broad feet of Ambulocetus hint that it moved more like an otter or sea lion on land than its terrestrial ancestors.

Kutchicetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3b/90/3b9043b3-e871-40a9-a441-5349e38af55b/kutchicetus_bw.jpg)

Early whale evolution is not a simple story of mammals that became better and better adapted to life in the water. Rather than a straight line of progress, the oldest part of the whale family tree has many different branches representing forms that were quite at home living between land and water. Among them is the 46-million-year-old Kutchicetus.

Like many early whales, Kutchicetus was a roughly wolf-size animal that lived in brackish habitats along shores of what’s now India and Pakistan. Its snout is exceptionally long and shallow, good for snapping quickly at slippery prey. Based on the mammal’s limbs and hips, paleontologists think Kutchicetus could still support its weight on land but lived much as otters do, undulating in the water in search of small morsels before coming out of the prehistoric pool to warm its fur in the sun.

Maiacetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0a/b3/0ab3dfff-12ee-4ffe-b2f7-2a712bfa2fb8/adult_female_and_fetal_maiacetus_web.jpg)

Adapting to life at sea required more of early whales than shifting their swimming techniques. All modern whales give birth at sea, their offspring emerging into the world tail-first to help prevent them from drowning as a head-first birth would risk. When this shift happened is unclear, but the skeleton of the “mother whale” Maiacetus indicates that it was after 47.5 million years ago.

Maiacetus was more adept in the water than earlier whales. Its spine was flexible for up-and-down swimming motions, and its digits were flatter, implying webbing in life. But one specimen included what has been interpreted as a fetus, in a position that suggests it would have been born head-first on land. Even as whales were becoming better and better swimmers, they still had to return to land to give birth.

Phiomicetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f9/99/f99930ca-5a0f-4c60-b8cf-093188f2ca53/phiomicetus_web.jpg)

The coasts of what are now Pakistan and India were a crucial place for whale origins. The earliest whales and their ancestors are found there in rocks more than 50 million years old. But by about 43 million years ago, whales were straying farther and farther from familiar shores. Phiomicetus from Egypt marks the early days of when whales began spreading throughout earth’s marine realm.

In life, Phiomicetus would have been about ten feet long. On land, the whale could walk but only in an awkward and clumsy way, sticking close to the water where it was more comfortable swimming just as seals stay close to the water today. Like other related whales, it had conical, grabbing teeth toward the front of the jaw and shearing teeth at the cheek. Along with clues from the whale’s skull that hint at strong muscle attachments, paleontologists think Phiomicetus had a powerful bite it relied upon to prey upon sharks, turtles and maybe other early whales.

Georgiacetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0f/0e/0f0e1771-34a9-4295-bba6-12e81431aa05/georgiacetus_bw.jpg)

Whales began crossing oceans when they still had legs. Fossils dating to about 40 million years ago from the southeastern United States leave no doubt. Georgiacetus, first found in Georgia, looks very similar to whales like Maiacetus found in India and Pakistan but must have crossed the ancient Atlantic to get there.

Like Maiacetus, the seal-size Georgiacetus belonged to an early whale group called protocetids. They still had arms and legs with paddle-like hands and feet, but their spines had become more flexible to undulate and push them through the water. So far as paleontologists can tell, Georgiacetus did not have a tail fluke like modern whales but was still a strong enough swimmer to cross vast ocean distances. In fact, paleontologists have hypothesized that the hind limbs of Georgiacetus were no longer as important for moving on land as acting like rudders in the water, the whale’s hips only barely connected to the spine. If future finds confirm the notion, it may be that Georgiacetus spent little, if any, time on land and was mostly aquatic while still having legs.

Peregocetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/de/0ddeefdd-bfd6-4884-9584-5d30971ae58e/196940_web.jpg)

Once early whales were able to swim and survive in the open ocean, they began spreading all over the world. Around the same time as Georgiacetus was swimming through waters over what’s now the southeastern U.S., the similar Peregocetus was living along the coast of prehistoric Peru.

So far, Peregocetus is known from the partial skeleton of a single animal. The bones show that the hips of the animal could still hold up the whale’s weight on land, yet, like seals and sea lions, the living animal was likely more graceful in the water than on land. While future finds may adjust the story, Peregocetus and related species from North America indicate whales were spreading worldwide within ten million years after early forms like Pakicetus began to dip their toes in the water.

Pappocetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/37/5a/375a7e6f-5b6c-4690-99e1-42507f1169a7/pappocetus_lugardi_reconstructed_skull.jpg)

For millions of years, multiple species of early whales swam in the same waters. Among waters that once covered what’s now Morocco, about 40 million years ago, as many as six different early whale species lived in the same area and came in a range of sizes. Among the largest was Pappocetus, a whale with legs that grew exceptionally larger than those of most of its relatives.

Precisely how long Pappocetus was is unclear. But a hip bone shows that it could have fit a femur, or thigh bone, that was over two inches in diameter at the top. The measurement is larger than for any other protocetid and suggests Pappocetus rivaled the fully aquatic whale Basilosaurus, which stretched over 50 feet, in length. The finding indicates that protocetids could attain huge sizes and overlapped in size, habitat and likely diet with the fully aquatic whales that came after them. Given its size and changes to the hips and legs inherited from its ancestors, Pappocetus would have only been able to move along the sand in a seal-like fashion and likely spent most if not all of its time in the water.

Aegicetus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/85/56855239-b0ae-49e5-8400-de85b196eef8/aegicetus_cgm_60584_skeleton_web.jpg)

Living whales only have the barest remnants of their hind limbs remaining, vestigial bones hidden within their bodies. The 35-million-year-old Aegicetus from Egypt marks when whales had become so adept at moving through the water they left land behind despite still having hind legs.

While Aegicetus looks quite a bit like other early whales such as Maiacetus and Georgiacetus, its legs were even smaller and had comparatively tiny hind feet. The broad, likely webbed feet of this early whale would have helped it waddle and push itself along sandy beaches and tidal flats, but by this point whales had left running on land far behind. The limbs may have helped with steering, but clearly they were no longer important for propulsion. Instead, Aegicetus and the whales that would come after would rely on movements and the thrust of their tails to get through the water.

Full Caption for Main Image: Nobu Tamura via Wikipedia under CC By 3.0 / Nobu Tamura via Wikipedia under CC By 3.0 /Nobu Tamura via Wikipedia under CC By 3.0 / Nobu Tamura via Wikipedia under CC By 3.0 / A. Gennari

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

Riley Black – Science Correspondent